Se han modificado 37 ficheros con 1257 adiciones y 735 borrados

Dividir vista

Opciones de diferencias

-

+229 -115content/analysis.tex

-

+8 -8content/appendix_test_cases.tex

-

+40 -39content/background.tex

-

+46 -52content/case_evaluation.tex

-

+20 -6content/case_evaluation_result.tex

-

+7 -8content/case_experiment.tex

-

+37 -37content/case_experiment_end-effector.tex

-

+61 -44content/case_experiment_feature_definition.tex

-

+81 -66content/case_experiment_initial_design.tex

-

+3 -2content/case_experiment_problem_description.tex

-

+52 -44content/case_experiment_prototype.tex

-

+67 -49content/case_experiment_scara.tex

-

+11 -12content/case_experiment_specifications.tex

-

+21 -13content/case_experiment_test_protocol.tex

-

+38 -35content/case_method.tex

-

+162 -3content/conclusion.tex

-

+5 -5content/input/speclistc.tex

-

+1 -1content/input/systemtest1.tex

-

+1 -1content/input/systemtest6.tex

-

+38 -37content/introduction.tex

-

+203 -94content/reflection.tex

-

+0 -3content/samenvatting.tex

-

+33 -2content/summary.tex

-

BINfront.pdf

-

+27 -11graphics/design_flow.tex

-

+2 -2graphics/design_flow_analysis.tex

-

+1 -1graphics/electronics.tex

-

+13 -2graphics/functional_relation.tex

-

+3 -3graphics/model_versions.tex

-

+1 -1graphics/robmosys.tex

-

+24 -0graphics/robmosys_levels.tex

-

BINgraphics/scara_test.JPG

-

+2 -2graphics/test_flow_graph.tex

-

+15 -6graphics/time_table.tex

-

+0 -23graphics/waterfall.tex

-

+1 -1include

-

+4 -7report.tex

+ 229

- 115

content/analysis.tex

Ver fichero

| @@ -1,25 +1,30 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \chapter{Analysis} | |||

| \chapter{Design Plan} | |||

| \label{chap:analysis} | |||

| The previous chapter introduced how two design methods are combined to form the bases for one complete design method. | |||

| In this chapter, a design plan is created from this combined design method. | |||

| The goal is to have a concrete design plan that is used in the case study. | |||

| The goal of this chapter is to define a concrete design plan that is used in the case study. | |||

| All of the steps in the design plan must be specific such that each of these steps can be evaluated after the case study is finished. | |||

| The first three steps of the design phase are based on the \ac{se} approach and are already described with great extend by \textcite{blanchard_systems_2014}. | |||

| As the evaluation of \ac{se} is not in the scope of this thesis, this chapter only covers the minimal description of the design steps in \ac{se}. | |||

| The steps that are introduced by \ridm are covered in more detail. | |||

| The previous chapter introduced how two design methods are combined to form the basis of the design plan. | |||

| \section{Systems Engineering} | |||

| The goal of the preliminary design is to setup system requirements and an initial design according to the problem definition. | |||

| The design plan consists of two parts: | |||

| The first part is the Preliminary System Design and contains the linear set of steps from problem description to feature definition. | |||

| The second part is the Development Cycle, which contains the features selection, variable-detail approach and rapid development cycle. | |||

| \section{Preliminary Phase} | |||

| The goal of the preliminary design phase is to create a set of features for the design solution. | |||

| Although these design steps in \ac{se} play a crucial roll in the success of the development, they are, however, very exhaustive. | |||

| A major part of this complete design process is the required documentation to ensure agreement about the design between the different stakeholders. | |||

| Resulting in a process that can take months or even years, which is not feasible for this thesis. | |||

| In this thesis, this design plan is only used for evaluation and has only one stakeholder, the author. | |||

| This allows for a simple implementation of the \ac{se} approach, as it not possible to create a false start due to misunderstanding, saving valuable time. | |||

| For each of these \ac{se} steps is explained what is involved with a full implementation, and what part of the step is used in the design plan. | |||

| \subsection{Problem Definition} | |||

| Before any design process can start, the "problem" has to be defined. | |||

| The first three steps of the preliminary phase are based on the \ac{se} approach by \textcite{blanchard_systems_2014}. | |||

| As the evaluation of \ac{se} is not in the scope of this thesis, this chapter only covers the minimal description of the design steps in \ac{se}. | |||

| These three steps deliver requirements and an initial design. | |||

| The last two steps define the set of features and tests based on these deliverables. | |||

| \subsection{Problem Description} | |||

| Before any design process can start, the "problem" has to be described. | |||

| In other words, why is the function of the system needed? | |||

| This is described in a \emph{statement of the problem}. | |||

| In this statement of the problem it is important to describe "what" has to be solved, not directly "how". | |||

| @@ -34,7 +39,7 @@ The steps that are introduced by \ridm are covered in more detail. | |||

| As these characteristics form the foundation of the system, the requirements must be defined without any ambiguity, vagueness or complexity. | |||

| The requirements are written according to the \ac{ears} \autocite{mavin_easy_2009}. | |||

| \ac{ears} was chosen for this design method due to its simplicity, which fits the scope of this thesis. | |||

| Later in the design, these requirements are divided over the subsystems. | |||

| Later in the design, these requirements are distributed over the subsystems. | |||

| Any issues, like ambiguity, in the requirements, propagate through these subsystems. | |||

| This might lead to a redesign of multiple sub-systems when these requirements have to be updated. | |||

| @@ -46,71 +51,171 @@ The steps that are introduced by \ridm are covered in more detail. | |||

| The best alternative is materialized in a design document together with the system requirements. | |||

| This design document is used in the next phase of the design. | |||

| \section{Rapid Iterative Design Method} | |||

| From this point, the design plan is based on the \ridm and not anymore on the waterfall model. | |||

| The first step is the feature definition, which prepares the required features based on the initial design. | |||

| The features are defined by splitting the system in such a way that the results of each implemented feature are testable. | |||

| The definition of the feature contains a description and a set of sub-requirements which is used to implement and test the feature. | |||

| During the feature definition, the dependencies, risks and time resources are determined as well, this establishes the order of implementation in the feature selection step. | |||

| Based on the requirements of \ridm as explained in \autoref{chap:background}, the next step is the feature selection. | |||

| However, it became apparent that the number of tests related to a specific feature is a good metric for the selection step. | |||

| Because, at the point that a feature is implemented, the tests are completed as well, and when the tests of the complete system pass, the system meets the specifications. | |||

| Following the \ridm, these tests are specified at the start of the rapid development cycle. | |||

| This makes it impossible to use the tests during the feature selections. | |||

| Therefore, a test protocol step is added after the feature definition and before the feature selection step. | |||

| The third step is the feature selection, where one of the features is selected. | |||

| This selection is based on the dependencies, tests, risk, and time requirements in the feature definitions. | |||

| The fourth step is the rapid development cycle, which uses the sub-requirements and description of the selected feature to create an initial design and a minimal implementation. | |||

| In the last step, the variable detail approach is used to add detail to the minimal implementation over the course of multiple iterations. | |||

| The tests are used to determine if the added detail does not introduce any unexpected behavior. | |||

| This cycle of adding detail and testing is repeated till the feature is fully implemented. | |||

| From this point, the \ridm is repeated from the third step until all features are implemented. | |||

| %\section{Rapid Iterative Design Method} | |||

| % From this point, the design plan is based on the \ac{ridm} and not anymore on the waterfall model. | |||

| % The first step is the feature definition, which prepares the required features based on the initial design. | |||

| % The features are defined by splitting the system in such a way that the results of each implemented feature are testable. | |||

| % The definition of the feature contains a description and a set of sub-requirements which is used to implement and test the feature. | |||

| % During the feature definition, the dependencies, risks and time resources are determined as well, this establishes the order of implementation in the feature selection step. | |||

| % | |||

| % Based on the requirements of \ac{ridm} as explained in \autoref{chap:background}, the next step is the feature selection. | |||

| % However, it became apparent that the number of tests related to a specific feature is a good metric for the selection step. | |||

| % Because, at the point that a feature is implemented, the tests are completed as well, and when the tests of the complete system pass, the system meets the requirements. | |||

| % Following the \ac{ridm}, these tests are specified at the start of the rapid development cycle. | |||

| % This makes it impossible to use the tests during the feature selections. | |||

| % Therefore, a test protocol step is added after the feature definition and before the feature selection step. | |||

| % | |||

| % The third step is the feature selection, where one of the features is selected. | |||

| % This selection is based on the dependencies, tests, risk, and time requirements in the feature definitions. | |||

| % The fourth step is the rapid development cycle, which uses the sub-requirements and description of the selected feature to create an initial design and a minimal implementation. | |||

| % In the last step, the variable-detail approach is used to add detail to the minimal implementation over the course of multiple iterations. | |||

| % The tests are used to determine if the added detail does not introduce any unexpected behavior. | |||

| % This cycle of adding detail and testing is repeated till the feature is fully implemented. | |||

| % From this point, the \ac{ridm} is repeated from the third step until all features are implemented. | |||

| \subsection{Feature Definition} | |||

| \label{sec:featuredefinition} | |||

| During the feature definition, the system is split into features as preparation for the rapid development cycle and the variable-detail approach. | |||

| The goal of the \ridm is to get feedback of the design as early as possible by performing short implementation cycles. | |||

| To achieve these short cycles, the features that are implemented in these cycles, are as small as possible. | |||

| However, the features must still be implemented and tested individually during the implementation and can thus not be split indefinitely. | |||

| Together with the definition of the features, the requirements are divided along the features as well. | |||

| The optimal strategy on splitting features and specifications is strongly dependent on the type of system. | |||

| Therefore, the best engineering judgement of the developer the best tool available. | |||

| In some cases it is not possible to define a feature that can be implemented and tested independently. | |||

| This occurs when the feature is dependent on the implementation of other features. | |||

| This dependency can occur in specifications, where strength of one feature dictates the maximum mass of another feature. | |||

| Such a dependency can work both ways and can be resolved by strengthening the one feature, or reduce the weight of the other feature. | |||

| Another type of dependency is when the implementation influences other features. | |||

| In this case, if the implementation of one feature changes, it requires a change in the other features. | |||

| An example of this is a robot arm, where the type of actuation strongly influences the end-effector. | |||

| When the robot arm approaches an item horizontally, it requires a different end-effector than approaching the item vertically. | |||

| There are two important responsibilities for the developer when the design encounters feature dependency. | |||

| The first one is during the definition, where the developer has to decide on how to split the system and how the dependency is stacked. | |||

| For the specification and the implementation dependency the developer must evaluate the optimal order of dependency. | |||

| The developer must arrange the dependency of the features such that the influence on the dependent feature is as small as possible. | |||

| In other words, if feature A can be easily adapted to the implementation of feature B, but not the other way around, the developer must go for A dependent on B. | |||

| The second responsibility is organizing the feature requirements. | |||

| Due to these dependencies it is possible that the division of requirements changes, because the result of the implemented feature was not as expected. | |||

| This is not directly a problem, but a good administration of the requirements makes an update of these requirements easier. | |||

| During the feature definition step, the initial design is split into features as preparation for the rapid development cycle and the variable-detail approach. | |||

| The \ac{ridm} does not provide a particular approach to define the features of the design. | |||

| But, the goal is to have features that can be implemented and tested individually. | |||

| The approach in this design plan aims to provide a more guided and structured way to split the features. | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=21mm]{graphics/robmosys_levels.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Hierachical structure of functions and components. Each arrow represents a many-to-many relation.} | |||

| \label{fig:robmosys_levels} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| The approach to define features in this design plan is based on the separation of levels principle \autocite{noauthor_robmosys_2017}. | |||

| This principle defines different levels of abstraction. | |||

| This starts from the top with the \emph{mission}, for example, serving coffee. | |||

| Followed by less abstract levels such as: a \emph{task} to fill the coffee mug; a \emph{skill} to hold that mug; and a \emph{service} allows the hand to open or close. | |||

| The different levels allow the features to be split multiple times in a structured way. | |||

| Take the coffee serving example, to fill the coffee mug, it is not sufficient to only hold the mug. | |||

| The system also has to pour coffee into the mug, and maybe add sugar or milk. | |||

| This results in a hierarchical tree of functions as shown in \autoref{fig:robmosys_levels}. | |||

| Each of the levels have a many-to-many relation with each other. | |||

| With this approach, features are defined top-down and are implemented bottom-up. | |||

| Thus a \emph{skill} is defined as one or more \emph{services}. | |||

| When all the \emph{services} are implemented, they are combined into a \emph{skill}. | |||

| The advantage of this is that the \emph{skill} defines a milestone to combine the relevant \emph{services}. | |||

| Or looking at the example: the system must at least be able to grab, stir, and pour before it can fill a mug with coffee, milk and sugar. | |||

| Another advantages is that multiple \emph{skills} can have a \emph{service} in common. | |||

| This would be the case if our system also needs to serve tea. The system can already hold a mug and only needs the ability to add a teabag. | |||

| Even though there is no exact level of abstraction required for each of the features, it does create a structure for the developer. | |||

| In the end, the developer must rely on its engineering judgement to chose the optimal division between features. | |||

| The bottom level of the hierarchy is a special case as it describes hardware instead of functions. | |||

| The components are used to execute the functionality of the system with. | |||

| For example, having a mobile robot arm near a coffee machine does meet the hardware requirements, it does not have any functionality if that is not yet implemented. | |||

| This also creates a clear division for the developer as the functions cannot be mixed with the hardware. | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % As explained in the previous chapter, the goal of the \ac{ridm} is to get feedback on the design as early as possible. | |||

| % To achieve this, the design is split into features, and each feature is implemented and tested sequentially. | |||

| % Resulting in smaller development cycles that are tested individually. | |||

| % If a feature fails its test it occurs directly after its implementation, instead of when the full system is implemented. | |||

| % The goal of this step is to apportion the system into features. | |||

| % Each feature must be small but independent, meaning that the feature can still be individually implemented and tested. | |||

| % | |||

| % In some cases it is not possible to define a feature that can be implemented and tested independently. | |||

| % This occurs when the feature is dependent on the implementation of other features. | |||

| % This dependency can occur in requirements where, for example, strength of one feature limits the mass of another feature. | |||

| % Such a dependency can work both ways and can be resolved by strengthening one feature, or reduce the mass of the other feature. | |||

| % Another type of dependency is when the implementation influences other features. | |||

| % In this case, if the implementation of one feature changes, it requires a change in the other features. | |||

| % An example of this is a robot arm, where the type of actuation strongly influences the end-effector. | |||

| % When the robot arm approaches an item horizontally, it requires a different end-effector than approaching the item vertically. | |||

| % | |||

| % \subsubsection{Feature Hierarchy} | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % %%%%%%%% -> | |||

| % There are two important responsibilities for the developer when the design encounters feature dependency. | |||

| % The first one is that the developer must determine where to split the system. | |||

| % | |||

| % In case of a dependency, the developer must evaluate the optimal order of implementation. | |||

| % The developer must arrange the dependency of the features such that the influence on the dependent feature is as small as possible. | |||

| % In other words, if feature A can be easily adapted to the implementation of feature B, but not the other way around, the developer must go for A dependent on B. | |||

| % The second responsibility is organizing the feature requirements. | |||

| % Due to these dependencies it is possible that the division of requirements changes, because the result of the implemented feature was not as expected. | |||

| % This is not directly a problem, but a good administration of the requirements makes an update of these requirements easier. | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % | |||

| % To achieve these short cycles, the features that are implemented in these cycles, are as small as possible. | |||

| % However, the features must still be implemented and tested individually during the implementation and can thus not be split indefinitely. | |||

| % Together with the definition of the features, the requirements are divided along the features as well. | |||

| % The optimal strategy on splitting features and requirements is strongly dependent on the type of system. | |||

| % Therefore, the best engineering judgement of the developer the best tool available. | |||

| % | |||

| % In some cases it is not possible to define a feature that can be implemented and tested independently. | |||

| % This occurs when the feature is dependent on the implementation of other features. | |||

| % This dependency can occur in requirements, where strength of one feature dictates the maximum mass of another feature. | |||

| % Such a dependency can work both ways and can be resolved by strengthening the one feature, or reduce the weight of the other feature. | |||

| % Another type of dependency is when the implementation influences other features. | |||

| % In this case, if the implementation of one feature changes, it requires a change in the other features. | |||

| % An example of this is a robot arm, where the type of actuation strongly influences the end-effector. | |||

| % When the robot arm approaches an item horizontally, it requires a different end-effector than approaching the item vertically. | |||

| % | |||

| % There are two important responsibilities for the developer when the design encounters feature dependency. | |||

| % The first one is during the definition, where the developer has to decide on how to split the system and how the dependency is stacked. | |||

| % For the requirement and the implementation dependency the developer must evaluate the optimal order of dependency. | |||

| % The developer must arrange the dependency of the features such that the influence on the dependent feature is as small as possible. | |||

| % In other words, if feature A can be easily adapted to the implementation of feature B, but not the other way around, the developer must go for A dependent on B. | |||

| % The second responsibility is organizing the feature requirements. | |||

| % Due to these dependencies it is possible that the division of requirements changes, because the result of the implemented feature was not as expected. | |||

| % This is not directly a problem, but a good administration of the requirements makes an update of these requirements easier. | |||

| \subsection{Test protocol} | |||

| \label{sec:systemtesting} | |||

| During the rapid development cycle and the variable detail approach, the system is tested constantly. | |||

| During the rapid development cycle and the variable-detail approach, the system is tested constantly. | |||

| This is to make sure that the design still performs as expected. | |||

| The tests are based on the specifications. | |||

| Each specification must be covered with at least one test. | |||

| The tests are based on the requirements. | |||

| Each requirements must be covered with at least one test. | |||

| The tests consist of a description which specifies how to perform the test and what the result of the test must of must not be. | |||

| Together with the description, there is a list of required features to perform the test and a list of specifications that are met if the test passes. | |||

| Together with the description, there is a list of required features to perform the test and a list of requirements that are met if the test passes. | |||

| \section{Development Cycle} | |||

| The development cycle consists of three steps, which are repeated for each individual feature. | |||

| These three steps form the core of the \ac{ridm}. | |||

| This starts with selecting the feature that is to be implemented, which then is implemented with the rapid development and variable-detail approach. | |||

| \subsection{Feature Selection} | |||

| \label{sec:feature_selection} | |||

| The rapid development cycle does not specify which feature is implemented first, even though the order of implementation does change the feasibility of the complete development. | |||

| The goal of this section is to improve the features selection criteria of the \ac{ridm} | |||

| The \ac{ridm} states that critical features, those with a high \emph{\ac{cof}}, must be implemented first. | |||

| If a critical feature fails, it is at the start of the design process, thereby invalidating only a portion of the design process. | |||

| Features that are (time) expensive to implement, must be implemented as late as possible. | |||

| These expensive features have a high \emph{Cost of Change} and placing them at the end of the development avoids making changes to the features. | |||

| The \emph{\acl{cof}} and \emph{Cost of Change} are a good starting point for selection criteria. | |||

| However, this creates an interesting situation for features with both a high change of failure and a high cost of change. | |||

| The rest of this section provides a structured approach for feature selection. | |||

| An example that shows the importance of the order of features is the development of a car. | |||

| To have a critical damped suspension in a car, the weight distribution of the car must be known. | |||

| If the suspension of the car is designed before all the features that determine the weight distribution, it is likely that the suspension design is not up to specifications. | |||

| If the suspension of the car is designed before all the features that determine the weight distribution, it is likely that the suspension design is not up to requirements. | |||

| Resulting in a redesign of the suspension feature and thus increasing the overall development cost. | |||

| This example is caused by the dependency between different features. | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| @@ -119,60 +224,68 @@ The steps that are introduced by \ridm are covered in more detail. | |||

| \caption{Dependency graph for features.} | |||

| \label{fig:feature_dependency} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| \begin{table}[] | |||

| \caption{Comparison of features with their corresponding risk and time. | |||

| The last column is the risk value divided by the number of days.} | |||

| \begin{table*}[] | |||

| \caption{Comparison of features with their corresponding \ac{cof} and time. | |||

| The last column is the \ac{cof} value divided by the number of days.} | |||

| \label{tab:feature_selection} | |||

| \begin{tabular}{l|r|r|r|r|r|} | |||

| \cline{2-6} | |||

| & \multicolumn{1}{l|}{Dependees} & \multicolumn{1}{l|}{Tests} & \multicolumn{1}{l|}{Risk} & \multicolumn{1}{l|}{Time} & \multicolumn{1}{l|}{Risk per time} \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. A} & 2 (2, 3) & 2 & 15 \% & 3 days & 5 \\ \hline | |||

| & \multicolumn{1}{l|}{Dependees} & \multicolumn{1}{l|}{Tests} & \multicolumn{1}{p{0.13\paperwidth}|}{\acl{cof} (\acs{cof})} & \multicolumn{1}{l|}{Time} & \multicolumn{1}{p{0.13\paperwidth}|}{Change of Failure over time} \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. A} & 2 (B, C) & 2 & 15 \% & 3 days & 5 \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. B} & 0 & 3 & 40 \% & 5 days & 8 \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. C} & 1 (5) & 5 & 25 \% & 2 days & 12.5 \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. C} & 1 (E) & 5 & 25 \% & 2 days & 12.5 \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. D} & 0 & 4 & 15 \% & 1 day & 15 \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. E} & 0 & 4 & 45 \% & 6 days & 7.5 \\ \hline | |||

| \end{tabular} | |||

| \end{table} | |||

| \end{table*} | |||

| To determine the order of implementation of features, a dependency graph and a comparison table is made. | |||

| The dependency graph and the comparison table for a theoretic system is shown in \autoref{fig:feature_dependency} and \autoref{tab:feature_selection} respectively. | |||

| The comparison table has dependees column, that describes the number of features that are depending on that specific feature, and are derived from the dependency graph. | |||

| In general the dependency of the features is inherited from the hierarchical structure that is made in the feature definition step. | |||

| The comparison table has a dependees column, that describes the number of features that are depending on that specific feature, and are derived from the dependency graph. | |||

| The tests column describes the number of tests that are covered by implementing this feature. | |||

| These tests are defined during the initial design and the feature definition, the number represents the amount of tests that pass after implementation of the feature. | |||

| The risk per time score for third rule is calculated by dividing the risk score with the time score. | |||

| The goal of this score is to eliminate as much risk as possible in the least amount of time. | |||

| It seems logic to always implement the highest risk feature first, but it is possible to finish multiple features with a lower risk in the same time period. | |||

| This is visible in \autoref{tab:feature_selection}: In a time span of 6 days it is possible to implement feature E or features A, C, and D. | |||

| The risk that is cleared by E is 45 \% which is significantly less than the combined 65 \% of A, C and D. | |||

| Due to the limited scope of this thesis, it is not possible to give a good metric for determining risk and time. | |||

| The \ac{cof} per time score is calculated by dividing the \ac{cof} score with the time score. | |||

| The \ac{cof} score indicates the likeliness of unforeseen difficulties during the implementation of the feature. | |||

| The time score is an estimation about the required time for implementation. | |||

| This time score is strongly connected with the \emph{Cost of change}, but for readability I chose to refer to time instead. | |||

| Due to the limited scope of this thesis, it is not possible to give a good metric for determining \ac{cof} and time. | |||

| Nevertheless, it is strongly advised that the developer defines some metric that fits his project best. | |||

| With a completed table, the order of implementation of features is determined by the following rules: | |||

| It seems logic to always implement the feature with the highest \ac{cof}, but it is possible that the combined \ac{cof} of multiple features is higher for the similar time investment. | |||

| This is visible in \autoref{tab:feature_selection}: In a time span of 6 days it is possible to implement feature E or features A, C, and D. | |||

| The \ac{cof} for E is 45 \% which is significantly less than the combined 65 \%\footnote{This is not a valid approach to calculate the combined chance, but suffices for the goal of this example.} of A, C and D. | |||

| With a completed comparison table, the order of implementation for the features is determined by the following rules: | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \item Features that are dependencies of others must be implemented first. | |||

| \item Features that complete more system test than other features when implemented have priority. | |||

| \item Features with the higher \emph{risk per time} score than other features have priority. | |||

| \item Features with the higher \emph{\ac{cof} per time} score than other features have priority. | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| The rules are applied in order, if one rule reduces the set to a single feature to implement the rest of the rules are skipped. | |||

| The rules are applied in order. | |||

| If one rule reduces the set to a single feature, the rest of the rules are skipped. | |||

| The third rule is a sorting rule, and the feature that fits best is implemented. | |||

| In case of a draw or in special cases the developer decides what feature to implement next. | |||

| Looking at an example of 5 features: | |||

| As seen in \autoref{fig:feature_dependency}, Features B and C are dependent on feature A. | |||

| Feature D does not have any dependency connections, and feature E is dependent on C. | |||

| As shown in \autoref{fig:feature_dependency}, features B and C depend on feature A; | |||

| feature D does not have any dependency connections; | |||

| and feature E is dependent on C. | |||

| Together with the information in \autoref{tab:feature_selection}, the order of implementation is: | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Feature A:] has two features that are dependent on this feature, more than any other. | |||

| \item[Feature C:] has one feature that is dependent on this feature, most dependencies after A is implemented. | |||

| \item[Feature D:] has the same number of tests as E, but D has a significant higher risk per time score than E | |||

| \item[Feature C:] has one feature that is dependent on this feature, most dependees after A is implemented. | |||

| \item[Feature D:] has the same number of tests as E, but D has a significant higher \ac{cof} per time score than E | |||

| \item[Feature E:] has the most number of tests. | |||

| \item[Feature B:] only one left to be implemented. | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| Note that this example assumes that nothing changes. | |||

| In case of a feature not being feasible during the implementation, the design has to be reviewed. | |||

| This also means that the dependency graph and comparison table change, resulting in a different order of implementation. | |||

| This also means that the dependency graph and comparison table change, possibly resulting in a different order of implementation. | |||

| \subsection{Rapid Development Cycle} | |||

| \subsection{Rapid Development} | |||

| Each iteration of this rapid development cycle implements one complete feature. | |||

| The feature that is implemented is selected in the prior feature selection step. | |||

| The goal of this step is to lay the foundation for the development of the feature. | |||

| @@ -181,7 +294,7 @@ The set of detail elements is a collection of design aspects that are added to i | |||

| These detail elements can represent behavior, parasitic elements, or components. | |||

| How these detail elements are implemented and what the basic model consists of is based on the initial design of the selected feature. | |||

| The initial design of the feature is similar to the system wide approach in \autoref{sec:se_initial_design}. | |||

| The initial design of the feature is similar to the system-wide approach in \autoref{sec:se_initial_design}. | |||

| It consists of a design space exploration, but with more detail, which is possible as the feature is significantly smaller than the complete system. | |||

| From the design space exploration, the developer selects the optimal design choice for the current feature. | |||

| For this design choice, a design document is made that illustrates the rough shape and dynamics of the implementation. | |||

| @@ -193,60 +306,61 @@ In general, the basic elements should only represent dominant and essential beha | |||

| A good starting point for the dominant behavior is to identify the interesting energy states of the system. | |||

| The energy states of interest can include the energy states that are dominant, but also the states that are chosen by the developer. | |||

| These last states could represent the output states or status that have to be measured. | |||

| In the end, the developer decides if states are required and implement them in the basic model. | |||

| All the elements that are part of the initial design but are not part of the basic model are the detail elements. | |||

| In the end, the developer decides which states are required and implements them in the basic model. | |||

| All the elements that are part of the initial design but are not part of the basic model are classified as the detail elements. | |||

| Lets take a motorized double inverted pendulum for example, which consists of two arms with motorized joints. | |||

| Both pendulum arms are dominant energy states. | |||

| The electrical motors have also internal states, but store significantly less energy than the pendulum arms. | |||

| An basic model would in this case only consists of the arms, possibly even without any dynamic behavior. | |||

| The dynamic behavior, motor characteristics, resistance, or gravitational force are examples of detail elements that can be added to increase the detail. | |||

| The dynamic behavior, motor characteristics, resistance, or gravitational force are examples of detail elements to be added to increase the detail. | |||

| \subsection{Variable Detail Approach} | |||

| With the variable detail approach the basic model is developed into a refined model of the feature. | |||

| This is done by implementing the detail elements over the course of multiple iterations. | |||

| To determine the order of implementation of these elements the approach for the order of features from \autoref{sec:feature_selection}. | |||

| \subsection{Variable-Detail Approach} | |||

| With the variable-detail approach the basic model is developed into a refined model of the feature. | |||

| This is done by adding the detail elements over the course of multiple iterations. | |||

| Each iteration produces a new model with more detail than the previous. | |||

| The newly added detail is evaluated by performing the tests that were defined during the rapid development cycle. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=8.5cm]{graphics/test_flow_graph.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Decision flowchart to follow for failed tests on each detail level.} | |||

| \caption{Decision flowchart to follow for failed tests on each detail level. | |||

| Decision tree starts at the top left rectangle. | |||

| Depending on the questions, the next step of action is to continue with the design or review the design.} | |||

| \label{fig:test_flow_graph} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| Not all tests are expected to succeed from the start, as not all details are implemented. | |||

| For example, if the internal resistance of a electric motor is not yet implemented in the model, the motor can draw an unlimited current, and this would exceed the current draw specifications of the motor. | |||

| The decision flowchart in \autoref{fig:test_flow_graph} in determines whether the design must be reviewed or can continue on a failed test. | |||

| For example, if the internal resistance of a electric motor is not yet implemented in the model, the motor can draw unlimited current, and this would exceed the maximum current draw of the system. | |||

| The decision flowchart in \autoref{fig:test_flow_graph} determines whether the design must be reviewed or can continue on a failed test. | |||

| The decisions are made with the following questions: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item Passed Before? The current test of the current design failed, but was there a previous detail level where it passed? | |||

| \item Expected to fail? Does the test fail as a direct result from the added detail and was that intentional? | |||

| \item Expected to pass? Should the added detail to the model result in a pass of the test? | |||

| \item Will pass in future? Is there an element that will be implemented that results in a pass of the test? | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Passed Before?] The current test of the current design failed, but was there a previous detail level where it passed? | |||

| \item[Expected to fail?] Does the test fail as a direct result from the added detail and was that intentional? | |||

| \item[Expected to pass?] Should the added detail to the model result in a pass of the test? | |||

| \item[Will pass in future?] Is there an element to be implemented that results in a pass of the test? | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| In the case that the implementation of a detail element fails multiple times, the developer has to investigate if implementing the feature is still feasible. | |||

| This could result in a redesign of the feature or system. | |||

| When and how this decision has to be made differs per situation and is outside the scope of this thesis. | |||

| The developer must evaluate if there are feasible alternatives left for this element, feature or system, and apply these alternative if possible. | |||

| The developer must evaluate if there are feasible alternatives left for this element, feature or system, and apply these alternatives if possible. | |||

| When all detail elements are implemented and the basic model has evolved into a refined model of the feature, the design cycle moves back to the feature selection. | |||

| When all detail elements are implemented; all tests pass; and the basic model has evolved into a refined model of the feature, the design cycle moves back to the feature selection. | |||

| In the case that this is the last feature to implement, this concludes the development. | |||

| \section{Summary of Design Plan} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=6cm]{graphics/design_flow_analysis.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Combined design plan, based on the \ridm and the Waterfall model.} | |||

| \caption{Combined design plan, based on the \ac{se} and \ac{ridm} approach.} | |||

| \label{fig:design_plan_analysis} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| The waterfall model from \ac{se} and the \ridm \autocite{broenink_rapid_2019} are combined to create the design plan as shown in \autoref{fig:design_plan_analysis}. | |||

| The first five steps of the design process form the preparation phase: problem description, specifications, initial design, feature definition, and test protocol. | |||

| The initial design step creates a holistic design based on the prior problem description and specifications step. | |||

| The steps from \ac{se} and the \ac{ridm} are combined to create the design plan as shown in \autoref{fig:design_plan_analysis}. | |||

| The first five steps of the design process form the preparation phase: problem description, requirements, initial design, feature definition, and test protocol. | |||

| The initial design step creates a holistic design based on the prior problem description and requirements step. | |||

| The last step of the preparation is the feature definition, where the initial design is split into different features. | |||

| The resulting initial design and its features together form the design proposal for the development steps. | |||

| The last step of the preparation phase is the test protocol step, where the tests are defined to monitor the design process and validate that the system meets the specifications. | |||

| The development cycle consists of the feature selection, rapid development, and variable detail steps. | |||

| These three steps are applied to each feature in the initial design individually. | |||

| The last step of the preparation phase is the test protocol step, where the tests are defined to monitor the design process and validate that the system meets the requirements. | |||

| The development cycle consists of the feature selection, rapid development, and variable-detail steps. | |||

| These three steps are applied to each feature in the system individually. | |||

| With each iteration of the development cycle a new feature is added to the complete system. | |||

| All the tests of the individual features are performed in the complete system as well. | |||

| @@ -254,5 +368,5 @@ This ensures that the one feature does not break a another feature. | |||

| The design is finished when all the features are implemented, tested and combined. | |||

| In the optimal situation the preparation phase is only performed once at the start of the design, and the development cycle is performed for each feature. | |||

| However, if features prove to be infeasible, some steps have to be revised. | |||

| However, if features prove to be infeasible, some steps have to be revisited. | |||

+ 8

- 8

content/appendix_test_cases.tex

Ver fichero

| @@ -16,7 +16,7 @@ | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 1, 2, 6, 11, (12) | |||

| \item[Requirements:] 1, 2, 6, 11, (12) | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The Cable bot moved along the edge of the text area. | |||

| @@ -33,7 +33,7 @@ | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 7, 9, (12), 14, 15, 16 | |||

| \item[Requirements:] 7, 9, (12), 14, 15, 16 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item At the start and end of the test, the Cable bot does not move relative to the board. | |||

| @@ -52,7 +52,7 @@ | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 3, 4, (12), 13, 14 | |||

| \item[Requirements:] 3, 4, (12), 13, 14 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The SCARA wrote three characters on the whiteboard within \SI{2}{\second}. | |||

| @@ -68,7 +68,7 @@ | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector | |||

| \item[Specifications:] (5), (12), 17 | |||

| \item[Requirements:] (5), (12), 17 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item A tool is released from the end-effector and stored for later use. | |||

| @@ -90,7 +90,7 @@ | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector, Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 1, 2, 3, (12) | |||

| \item[Requirements:] 1, 2, 3, (12) | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item All lines are drawn, 11 vertical and 4 horizontal lines. | |||

| @@ -118,7 +118,7 @@ the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog!?@,.- | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector, Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 1, 2, 3, 4, (5), 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 | |||

| \item[Requirements:] 1, 2, 3, 4, (5), 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The text as described is readable from a atleast \SI{4}{\meter} distance. | |||

| @@ -133,7 +133,7 @@ the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog!?@,.- | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector, Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] (5), 10, 11, 12 | |||

| \item[Requirements:] (5), 10, 11, 12 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The system cleaned the board within \SI{60}{\second}. | |||

| @@ -147,7 +147,7 @@ the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog!?@,.- | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector, Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 8 | |||

| \item[Requirements:] 8 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The developer can motivate that the system is complex enough to evaluate the case study. | |||

+ 40

- 39

content/background.tex

Ver fichero

| @@ -1,38 +1,28 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \chapter{Background} | |||

| \chapter{Starting Point} | |||

| \label{chap:background} | |||

| Engineers have many different types of design methods available in their fields. | |||

| Examples of these are Agile, Spiral, V model, and Waterfall. | |||

| Each of these design methods start with a need and develop a product to satisfy that need. | |||

| From an extremely basic point of view, these methods start with a preliminary design where the need is translated into an initial design, requirements, and specifications. | |||

| This initial design is implemented into a product and the product is tested. | |||

| The preliminary design is often similar between the different design methods, but the methods differentiate on their implementation and testing phase. | |||

| \textcite{broenink_rapid_2019} do not provide a complete design method and focus on their implementation and testing method. | |||

| To create a complete design plan that can be used in the case study, I used the waterfall model in the \ac{se} approach as a basis for the design plan. | |||

| The techniques of the \ridm replace the implementation and testing phase of the waterfall model. | |||

| This chapter will introduce the basics of \ac{se} and the waterfall model, and analyse what the \ridm provides. | |||

| The goal of the design plan is to develop a \ac{cps}. | |||

| Due to the nature of \ac{cps}, it involves a multi-domain design approach. | |||

| Therefore, the subject of \ac{se} is relevant to this approach. | |||

| Furthermore, the \ac{ridm} is discussed in more detail in this chapter. | |||

| The \ac{ridm} does not initiate from the problem description step. | |||

| As this step is required a design from scratch, the \ac{ridm} is combined with the approach from \ac{se} establish the required design steps. | |||

| \section{Systems Engineering} | |||

| \label{sec:SE} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=2.9cm]{graphics/waterfall.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Minimalistic implementation of waterfall model.} | |||

| \label{fig:waterfall} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| \textcite{blanchard_systems_2014} describe \ac{se} in their book as: "an interdisciplinary approach and means to enable the realization of successful systems." | |||

| Their book extensively covers multiple design methods and design steps in detail. | |||

| The simplest of these design method is the waterfall model. | |||

| This waterfall model consists of number of steps that are all successively executed as shown in \autoref{fig:waterfall}. | |||

| The successive steps make it possible to insert or replace the steps in the design method. | |||

| For this thesis, their approach on \emph{Bringing a Systems into Being} and \emph{Preliminary System Design} are especially relevant. | |||

| \ac{se} is a complete field of engineering on its own and only the top of the iceberg is used in this thesis. | |||

| \section{Rapid Iterative Design Method} | |||

| \label{sec:RIDM} | |||

| The \ridm by \textcite{broenink_rapid_2019} describes a methodology using two core components for the implementation: the rapid development cycle and the variable detail approach. | |||

| The \ac{ridm} by \textcite{broenink_rapid_2019} describes a methodology using two core components for the implementation: the rapid development cycle and the variable-detail approach. | |||

| The design method also describes the preparation steps that are required prior to this implementation. | |||

| In short, the preparation prepares a list of features. | |||

| These features are implemented one by one with in the rapid development cycle using the variable detail approach. | |||

| This section discusses each of these three parts and how they fit in the waterfall model. | |||

| These features are implemented one by one with in the rapid development cycle using the variable-detail approach. | |||

| The following sections discus each of these three design steps. | |||

| \subsection{Rapid Development Cycle} | |||

| \label{sec:background_rdc} | |||

| @@ -44,35 +34,46 @@ Each iteration of the rapid development incorporates the following steps: | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| The first step is to create an initial design and tests that are used to verify the requirements of the current feature. | |||

| During the second step, the initial design is developed into a detailed design of the feature. | |||

| This detailed design of the feature is develop with the variable detail approach, in which the level of detail is stepwise incremented. | |||

| This detailed design of the feature is develop with the variable-detail approach, in which the level of detail is stepwise incremented. | |||

| When the second step is completed, the implemented feature contains all the required details and passes all the tests as defined in the first step. | |||

| From this point the rapid development cycle is repeated for the next feature, or, when no features are left, finish the development. | |||

| \subsection{Variable Detail Approach} | |||

| The variable detail approach starts with a low-detailed model and increases the detail discretely over multiple iterations. | |||

| \subsection{Variable-Detail Approach} | |||

| The variable-detail approach starts with a low-detailed model and increases the detail discretely over multiple iterations. | |||

| The low-detailed model is for example a single transfer function of the system. | |||

| In the following iteration, the detail of the model is increased by adding, for example, non-linearity, non-continuity or parasitic elements. | |||

| The tests, as specified in the first step of the rapid development cycle, are performed after each addition of detail. | |||

| If the tests show that the added detail is not conform the specifications, the added detail is reviewed or redesigned. | |||

| If the tests show that the added detail is not conform the requirements, the added detail is reviewed or redesigned. | |||

| When the added detail passes the tests, the process is repeated to add more detail. | |||

| The variable detail approach is finished when all the tests are passed and all the detail is added. | |||

| The variable-detail approach is finished when all the tests are passed and all the detail is added. | |||

| \subsection{Preparation steps} | |||

| Although the \ac{ridm} does not specify the complete steps for the preparation, it does state some requirements. | |||

| The rapid development cycle requires a list of features that can be implemented and tested individually. | |||

| These features are gained by partitioning the functionality of the system. | |||

| \subsection{Preparation} | |||

| Although the \ridm does not specify the complete steps for the preparation, it does state some requirements. | |||

| The rapid development cycle requires a list of features that can be implemented one by one. | |||

| These features are gained by partitioning the functionality of the system, such that features can be implemented and tested individually. | |||

| For each feature it is required to specify the feature requirements and the corresponding test protocol. | |||

| The feature requirements are based on the system requirements and the tests are used to validate that the feature meets its requirements. | |||

| About the order of implementation, the \ridm states that critical features should be implemented first, as these features have an increased chance of invalidating the complete design. | |||

| About the order of implementation, the \ac{ridm} states that critical features must be implemented first, as these features have an increased chance of invalidating the complete design. | |||

| Would such a feature fail, the investment loss is limited, because the development is still in an early stage. | |||

| \section{Combination} | |||

| Following the feature separation step is the system test protocol. | |||

| The goal of this step is to describe how the requirements of the system are tested. | |||

| These tests can cover a single feature or multiple features. | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=6cm]{graphics/design_flow.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Combined design plan, where the first three steps are based on the waterfall model and the other four steps are taken from the \ac{ridm} \autocite{broenink_rapid_2019}} | |||

| \includegraphics[width=55mm]{graphics/design_flow.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Combined design plan, where the first three steps are based on the \ac{se}-approach and the other four steps are taken from the \ac{ridm} \autocite{broenink_rapid_2019}} | |||

| \label{fig:design_flow} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| As the \ridm integrates the implementation and testing steps together, it replaces these steps in the waterfall model. | |||

| The first three steps as seen in \autoref{fig:waterfall} are unchanged and the last two steps are replaced by the \ac{ridm}. | |||

| A combined design flow of the both design methods is shown in \autoref{fig:design_flow}. | |||

| \section{Combination} | |||

| To create a complete design plan, design approaches from both \ac{se} and the \ac{ridm} are combined. | |||

| The \ac{ridm} requires an initial design that is then split into features. | |||

| To meet this requirement, a linear set of steps from problem description to initial design is used from \ac{se}. | |||

| These three steps are shown at the top of \autoref{fig:design_flow} in the \acl{se} group. | |||

| The steps show some similarity with the first steps of a V or Waterfall model. | |||

| The requirements and initial design are used in the four steps of \ac{ridm} continue the design process. | |||

| These four steps are grouped at the bottom of \autoref{fig:design_flow}. | |||

+ 46

- 52

content/case_evaluation.tex

Ver fichero

| @@ -1,75 +1,67 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \chapter{Case Study: Evaluation} | |||

| \label{chap:case_evaluation} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=51mm]{graphics/model_versions.pdf} | |||

| \caption{ | |||

| Levels of detail of the design are shown on the right, starting with the least detail at the top and most detail at the bottom. | |||

| Through out the development different types of models are used, these are shown on the left. | |||

| } | |||

| \label{fig:levels} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| The previous chapter described the development and implementation process of the Whiteboard Writer. | |||

| This chapter focusses on the evaluation of the development during the case study. | |||

| The design method itself is evaluated in the next chapter. | |||

| However, some of the topics discussed in this chapter have a strong overlap with those in the next chapter. | |||

| The first section gives a short overview of results of the case study. | |||

| Then a section is about the time spend on the development. | |||

| Followed by two sections on the role of stake holders and the use of modelling languages during a development. | |||

| The last section is a more personal reflection about the development. | |||

| \section{Result} | |||

| \input{content/case_evaluation_result.tex} | |||

| The first section is about the time spend on the development. | |||

| Followed by a section about the role of stake holders and one about the use of modelling languages during a development. | |||

| The last section is a more personal reflection about the case study. | |||

| \section{Time Investment} | |||

| \label{sec:time_investment} | |||

| Prior to each step in the development, I made an estimation on the workload of that particular step. | |||

| In \autoref{fig:time_spend} the planned and spend time on each step are plotted next to each other. | |||

| Five of these steps were completed in the planned number of days. | |||

| However, three steps required more time than expected. | |||

| As evaluated in \autoref{sec:case_featuredefinition_evaluation}, the proposed design method for the feature definition was not feasible. | |||

| Documenting and solving the problem resulted in a delay of seven days. | |||

| The second development cycle experienced a delay of four days. | |||

| This was a underestimation of the time needed to complete the step. | |||

| In addition to the steps, time was also spend on the hardware construction and software development. | |||

| The initial approach for the feature definition did not result in a statisfactory set of features. | |||

| Therefore, the approach for the feature definition was reformulated. | |||

| Before new approach was formulated, multiple attempts were made to get a representative set of features. | |||

| The time spend on performing the feature definition is not representative as formulating the new approach and creating the set of features were performed in parallel. | |||

| The real execution time is estimated to be around 3 to 5 days ( {\textsuperscript{1} in \autoref{fig:time_spend}). | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics{graphics/time_table.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Overview of the planned and spend number of days for each step during the case study. For Development Cycle 1 three days were planned for the initial development, based on the outcome I decided to abandon this cycle. Therefore, no additional time was planned nor spend on the development.} | |||

| \caption{ | |||

| Overview of the planned and spend number of days for each step during the case study. | |||

| Some of the values in this do not represent the time requirements of this design method:\newline | |||

| \textsuperscript{1} During the feature definition the design method was reviewed. | |||

| 13 days were spend on this review and execution, obfuscating the actual execution time. | |||

| The execution time is an estimated 3 to 5 days.\newline | |||

| \textsuperscript{2} The first cycle was cut short due to its complexity.\newline | |||

| } | |||

| \label{fig:time_spend} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| Furthermore, there is a significant difference between the planned number of days for both development cycles. | |||

| Furthermore, there is a significant time difference both development cycles. | |||

| Prior to the first development cycle I was not confident about the feasibility of the end-effector implementation. | |||

| Based on that, I decided to spend about three days on the basic model of the end-effector to collect more information. | |||

| This let me to the conclusion that the end-effector was too time-consuming for this case study. | |||

| Therefore, first development cycle was cut short ( \textsuperscript{2} in \autoref{fig:time_spend}) | |||

| For the second cycle, I also planned three days to create the basic model. | |||

| This time, the basic model was finished within a couple of hours. | |||

| Based this early success and prior experience, I planned an additional two weeks of development time for this cycle. | |||

| Based on this successful implementation and prior experience, I planned an additional two weeks of development time for this cycle. | |||

| Although not directly part of the design method, I did build a prototype. | |||

| This consisted of acquiring and assembling the hardware, and writing software. | |||

| To validate the design and model of the \ac{scara}, I build a prototype. | |||

| This consisted of building the hardware and writing software. | |||

| Acquiring and assembling the hardware took about two days. | |||

| This was mainly due to CoViD-19 restrictions which made part ordering and printing more challenging. | |||

| Without these restrictions I think it would be a day of work. | |||

| However, the time required to get the software to a viable state was four weeks. | |||

| Even though, the focus was not on the software, this timespan of four weeks is too significant to ignore. | |||

| The time required to get the software to a viable state was four weeks. | |||

| Even though the focus was not on the software, this timespan of four weeks was too significant to ignore. | |||

| Especially when the software is compared to the developed models. | |||

| As explained in the previous section, I build a total of eight models. | |||

| Each of these models includes documentation and an evaluation of the design process. | |||

| The software, on the other hand, is in a bare minimum state; I skipped documentation and evaluation; and the code quality relatively low. | |||

| Still, the software was more time consuming than the hardware modeling and development. | |||

| \textcite{royce_managing_1970} also acknowledges this difference in complexity for soft- and hardware. | |||

| He expects 50 pages of software documentation for each page of hardware documentation in projects with comparable budget. | |||

| \textcite{sheard_718_1998} discusses multiple points about the difference between soft- and hardware. | |||

| The point that is most applicable to this case study is that pure-hardware solution are relatively simple in their problem-space perspective. | |||

| However, the hardware solution is often complex in the solution space perspective. | |||

| The inverse is true for software. | |||

| Thus, a complex system is easier to implement with software. | |||

| \section{One-man development team} | |||

| The case study was performed by me, as a single developer. | |||

| The case study was performed by me as a single developer. | |||

| Against all expectations, this one-man development team made the preparation phase more difficult instead of easier. | |||

| The goal of the problem description and the requirements step is to get the stakeholders on the same line \autocite{shafaat_exploring_2015}. | |||

| This involves creating agreed-upon requirements for the system, but with only one stakeholder, this agreement is implicit. | |||

| @@ -77,7 +69,7 @@ The last section is a more personal reflection about the development. | |||

| Part of this is that there is no penalty for future reviews of the requirements, as I already agreed. | |||

| Furthermore, specific details and decisions were often made subconsciously, while I was commuting, waiting in line, or even showering. | |||

| Making structured documentation of these decisions at a later point in time without missing any of them was impossible. | |||

| Making structured documentation of these decisions at a later point in time without missing any of them is impossible. | |||

| The social interaction within a design team stimulates this documenting process as it improves the recall and interpretation of information. | |||

| It also improves the judgement and selection of design alternatives \autocite{lamb_221_2008}. | |||

| @@ -93,12 +85,12 @@ The last section is a more personal reflection about the development. | |||

| Resulting in a fourth model which represents the mechanical component design, in the form of a CAD drawing. | |||

| There are a couple of problems with this approach. | |||

| Implementing the same model with a different modelling approach, makes both models incompatible with each other. | |||

| Implementing the same model with two different modelling approaches, makes both models incompatible with each other. | |||

| This removes the possibility to switch back to a lower detail implementation. | |||

| Additionally, it creates the possibility to transfer parameters incorrectly from one model to another. | |||

| Such a switch is also labor intensive as the complete model has to be build from scratch again. | |||

| Furthermore, there is the possibility that this new model has been for nothing, as the planned detail proves to be unfeasible. | |||

| The point is, a future iteration of the design method must avoid these type of model switches. | |||

| The point is, a future iteration of the design method must minimize these type of model switches to reduce the chance of implementation errors. | |||

| \section{Reflection} | |||

| In the following section, I reflect on my own impact on the development. | |||

| @@ -106,11 +98,11 @@ The last section is a more personal reflection about the development. | |||

| \subsection{Preparation phase} | |||

| During the preparation phase often I had difficulty with getting the required information. | |||

| The information was often not specific enough or it it was overlooked. | |||

| The information was often not specific enough or it was overlooked. | |||

| Even though attempting to be thorough, requirements were never really specific. | |||

| As explained in the previous section, the lack of stake-holders is one of the reasons for information not being specific. | |||

| Furthermore, during the preparation information was often overlooked. | |||

| Resulting in a situation where I needed information that should have been the result of a previous step, which was not the case. | |||

| Information that was overlooked created a situation where I needed information that should have been the result of a previous step, which was not the case. | |||

| In most situations it was possible to continue with the execution of the step. | |||

| However, during the test protocol step (\autoref{sec:test_protocol}) it was not possible to continue. | |||

| Resulting in additional requirements added to the design, before continuing with the design process. | |||

| @@ -120,7 +112,7 @@ The last section is a more personal reflection about the development. | |||

| Being inexperienced does definitely not aid the design process. | |||

| Needless to say, more experience would improve the information situation. | |||

| However, it does not solve the problem. | |||

| Further improvements for the design method is required, to improve the information process during development. | |||

| Further improvements for the design method are required to improve the information process during development. | |||

| \subsection{Development phase} | |||

| \label{sec:evaluation_reflection_development} | |||

| @@ -132,8 +124,7 @@ The last section is a more personal reflection about the development. | |||

| For example, the \ac{scara} and the \ac{cdc} both include two stepper motors. | |||

| When I add detail to the stepper motor model, the \ac{scara} and the \ac{cdc} would then be updated as well. | |||

| However, each sub-model has to be updated manually. | |||

| In total four times in case of the stepper motor. | |||

| Which makes this workflow very labor intensive. | |||

| In total four times in case of the stepper motor, which makes this workflow very labor intensive. | |||

| A workflow that enables easy combination and interchange of sub-models is beneficial with this design method. | |||

| It makes it easy to evaluate the latest changes, by comparing them with previous versions. | |||

| @@ -143,12 +134,15 @@ The last section is a more personal reflection about the development. | |||

| \subsection{Continuation of this Case Study} | |||

| \label{sec:evaluation_reflection_protoype} | |||

| At the point that the SCARA was implemented, I gathered so much new information that the some of the design choices felt obsolete. | |||

| Although, the current design method does not incorporate a prototype, the current state of the design is more or less a prototype. | |||

| At the point that the \ac{scara} was implemented, I gathered so much new information that some of the design choices felt obsolete. | |||

| In this case study, the prototype is used to validate the design. | |||

| However, the current prototype contains so much information that it would improve the requirements and initial design significantly. | |||

| Following the current design plan, the next step would be to develop the \ac{cdc}. | |||

| In theory, if I would continue the case study, my proposal is to consider the current design as an actual prototype and revisit the preparation phase. | |||

| With the current knowledge, the specifications and initial design would improve significantly. | |||

| However, it is very important to note that this decision relies on the fact that the prototype is already created. | |||

| In other words, the work is already done and resulted in useful information for a next design iteration. | |||

| But, in case of a different system, I doubt that creating a prototype, followed by a full repeat of the design method is an efficient approach. | |||

| Therefore, the choice to revisit the preparation phase must not be considered as an improved design method but as an argument to improve the preparation phase itself. | |||

| In case of a different system, I doubt that creating a prototype, followed by a full repeat of the design method is an efficient approach. | |||

| Therefore, the choice to revisit the preparation phase must not be considered as an improved design method but as an argument to improve the preparation phase itself. | |||

| However, I think that an improved preparation phase must be shorter and incorporate a prototype. | |||

+ 20

- 6

content/case_evaluation_result.tex

Ver fichero

| @@ -1,13 +1,27 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \section{Result} | |||

| \label{sec:result} | |||

| In the end, the development produced eight models with increasing levels of detail and one prototype. | |||

| The different levels of detail and how they are modelled are shown in \autoref{fig:levels}. | |||

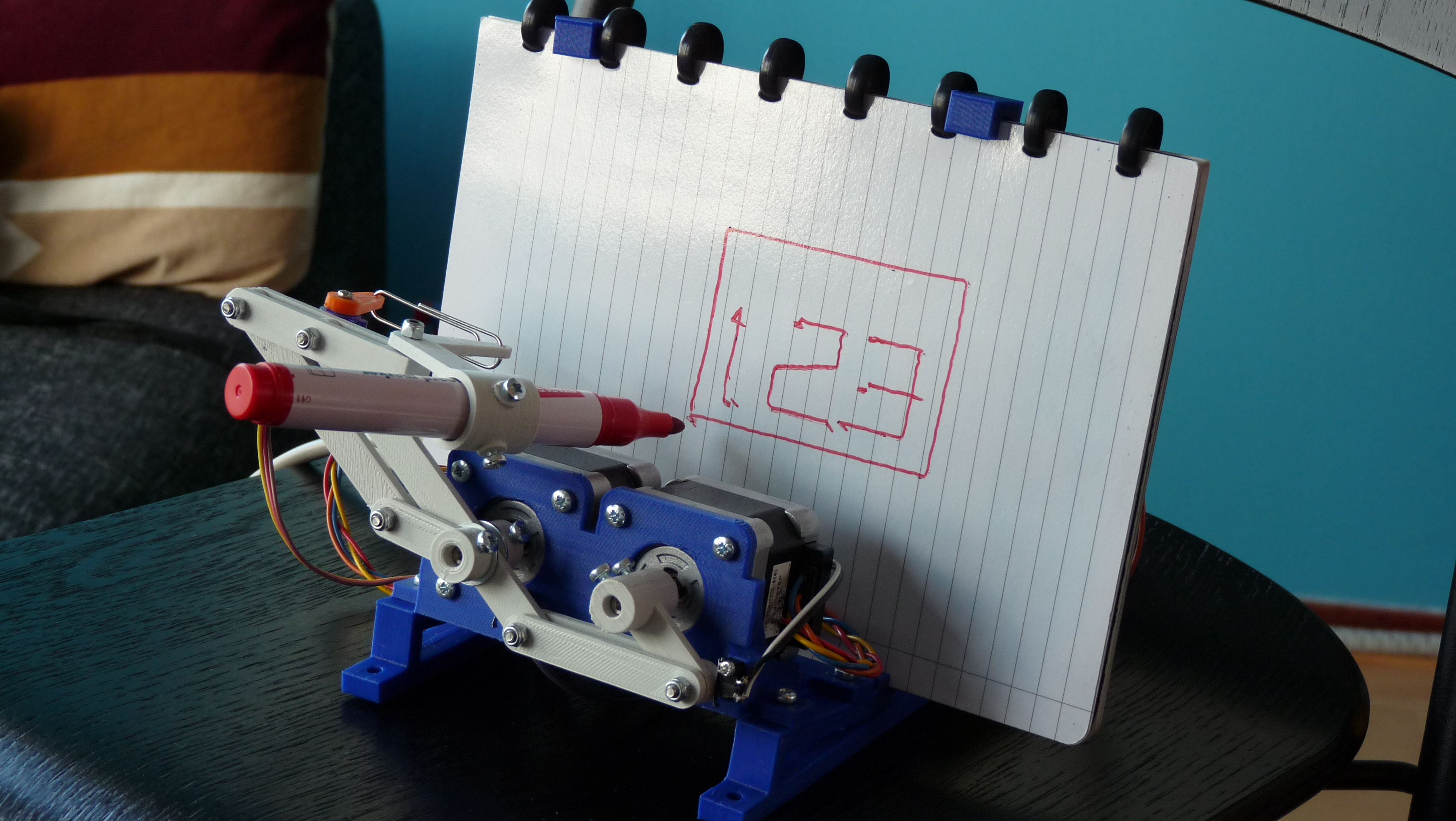

| The assembled \ac{scara} prototype is shown in \autoref{fig:prototype}. | |||

| This prototype is able execute the small rectangle as described in \autoref{test1}, and thus passes the test. | |||

| As the \ac{cdc} was not finished, a small stand was build to test the \ac{scara}. | |||

| The assembled \ac{scara} prototype on the stand is shown in \autoref{fig:prototype}. | |||

| This prototype is able to execute the small rectangle as described in \autoref{test1}, and thus passes the test. | |||

| In addition, it was possible to write three characters. Therefore, passing \autoref{test_triple_char}. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=51mm]{graphics/model_versions.pdf} | |||

| \caption{ | |||

| Levels of detail of the design are shown on the right, starting with the least detail at the top and most detail at the bottom. | |||

| Through out the development different types of models are used, these are shown on the left. | |||

| } | |||

| \label{fig:levels} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| \begin{figure*}[t] | |||

| \hspace{5mm} | |||

| \includegraphics[width=96mm]{graphics/prototype.JPG} | |||

| \caption{Assembled prototype of the \ac{scara}.} | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{graphics/scara_test.JPG} | |||

| \caption{Assembled prototype of the \ac{scara}. The \ac{scara} passed \autoref{test1} drawing the perimeter and passed \autoref{test_triple_char} with the characters $123$.} | |||

| \label{fig:prototype} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{figure*} | |||

+ 7

- 8

content/case_experiment.tex

Ver fichero

| @@ -4,23 +4,23 @@ | |||

| This chapter presents the execution of the case study. | |||

| Where the goal of the case study is to evaluate the design plan as presented in \autoref{chap:analysis}. | |||

| To achieve this goal, I develop a system according to the design plan and document this design process. | |||

| As described in \autoref{sec:sod}, the system to be designed is a "Tweet on a Whiteboard Writer". | |||

| As described in \autoref{sec:sod}, the subject of design is a "Tweet on a Whiteboard Writer". | |||

| Documenting the process is done by following the evaluation protocol as described in \autoref{sec:evaluation_protocol}. | |||

| To start the case study unbiased, during the preparation I did perform as little preliminary research as possible on the design options of the whiteboard writer. | |||