Kaynağa Gözat

Merge branch 'evaluation' into 'master'

Evaluation See merge request horlingsw/master-assignment-report!15merge-requests/15/merge

8 değiştirilmiş dosya ile 326 ekleme ve 88 silme

Görünümü Böl

Diff Seçenekleri

-

+3 -2content/background.tex

-

+141 -2content/case_evaluation.tex

-

+13 -0content/case_evaluation_result.tex

-

+33 -42content/case_experiment_feature_definition.tex

-

+49 -42content/case_experiment_test_protocol.tex

-

+47 -0graphics/model_versions.tex

-

BINgraphics/prototype.JPG

-

+40 -0graphics/time_table.tex

+ 3

- 2

content/background.tex

Dosyayı Görüntüle

| @@ -13,6 +13,7 @@ The techniques of the \ridm replace the implementation and testing phase of the | |||

| This chapter will introduce the basics of \ac{se} and the waterfall model, and analyse what the \ridm provides. | |||

| \section{Systems Engineering} | |||

| \label{sec:SE} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=2.9cm]{graphics/waterfall.pdf} | |||

| @@ -33,7 +34,7 @@ These features are implemented one by one with in the rapid development cycle us | |||

| This section discusses each of these three parts and how they fit in the waterfall model. | |||

| \subsection{Rapid Development Cycle} | |||

| The rapid development cycle consists of multiple iterations, where each iteration implements and tests one feature, that was defined during the preparation. | |||

| The goal of the rapid development cycle is sequential implementation of the features in a system. | |||

| Each iteration of the rapid development incorporates the following steps: | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \item Create an initial design and corresponding tests for the next feature. | |||

| @@ -57,7 +58,7 @@ The variable detail approach is finished when all the tests are passed and all t | |||

| \subsection{Preparation} | |||

| Although the \ridm does not specify the complete steps for the preparation, it does state some requirements. | |||

| The rapid development cycle requires a list of features that can be implemented one by one. | |||

| These features are gained by splitting the system into individual subsystems, where each subsystem can be implemented and tested individually. | |||

| These features are gained by partitioning the functionality of the system, such that features can be implemented and tested individually. | |||

| For each feature it is required to specify the feature requirements and the corresponding test protocol. | |||

| The feature requirements are based on the system requirements and the tests are used to validate that the feature meets its requirements. | |||

| About the order of implementation, the \ridm states that critical features should be implemented first, as these features have an increased chance of invalidating the complete design. | |||

+ 141

- 2

content/case_evaluation.tex

Dosyayı Görüntüle

| @@ -1,3 +1,142 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \chapter{case evaluation} | |||

| \label{case_evaluation} | |||

| \chapter{Case Study: Evaluation} | |||

| \label{chap:case_evaluation} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=51mm]{graphics/model_versions.pdf} | |||

| \caption{ | |||

| Levels of detail of the design are shown on the right, starting with the least detail at the top and most detail at the bottom. | |||

| Through out the development different types of models are used, these are shown on the left. | |||

| } | |||

| \label{fig:levels} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| The previous chapter described the development and implementation process of the Whiteboard Writer. | |||

| This chapter focusses on the evaluation of the development during the case study. | |||

| The design method itself is evaluated in the next chapter. | |||

| However, some of the topics discussed in this chapter have a strong overlap with those in the next chapter. | |||

| The first section gives a short overview of results of the case study. | |||

| Then a section is about the time spend on the development. | |||

| Followed by two sections on the role of stake holders and the use of modelling languages during a development. | |||

| The last section is a more personal reflection about the development. | |||

| \section{Result} | |||

| \input{content/case_evaluation_result.tex} | |||

| \section{Time Investment} | |||

| Prior to each step in the development, I made an estimation on the workload of that particular step. | |||

| In \autoref{fig:time_spend} the planned and spend time on each step are plotted next to each other. | |||

| Five of these steps were completed in the planned number of days. | |||

| However, three steps required more time than expected. | |||

| As evaluated in \autoref{sec:case_featuredefinition_evaluation}, the proposed design method for the feature definition was not feasible. | |||

| Documenting and solving the problem resulted in a delay of seven days. | |||

| The second development cycle experienced a delay of four days. | |||

| This was a underestimation of the time needed to complete the step. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics{graphics/time_table.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Overview of the planned and spend number of days for each step during the case study. For Development Cycle 1 three days were planned for the initial development, based on the outcome I decided to abandon this cycle. Therefore, no additional time was planned nor spend on the development.} | |||

| \label{fig:time_spend} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| Furthermore, there is a significant difference between the planned number of days for both development cycles. | |||

| Prior to the first development cycle I was not confident about the feasibility of the end-effector implementation. | |||

| Based on that, I decided to spend about three days on the basic model of the end-effector to collect more information. | |||

| This let me to the conclusion that the end-effector was too time-consuming for this case study. | |||

| For the second cycle, I also planned three days to create the basic model. | |||

| This time, the basic model was finished within a couple of hours. | |||

| Based this early success and prior experience, I planned an additional two weeks of development time for this cycle. | |||

| Although not directly part of the design method, I did build a prototype. | |||

| This consisted of acquiring and assembling the hardware, and writing software. | |||

| Acquiring and assembling the hardware took about two days. | |||

| This was mainly due to CoViD-19 restrictions which made part ordering and printing more challenging. | |||

| Without these restrictions I think it would be a day of work. | |||

| However, the time required to get the software to a viable state was four weeks. | |||

| Even though, the focus was not on the software, this timespan of four weeks is too significant to ignore. | |||

| Especially when the software is compared to the developed models. | |||

| As explained in the previous section, I build a total of eight models. | |||

| Each of these models includes documentation and an evaluation of the design process. | |||

| The software, on the other hand, is in a bare minimum state; I skipped documentation and evaluation; and the code quality relatively low. | |||

| Still, the software was more time consuming than the hardware modeling and development. | |||

| \textcite{royce_managing_1970} also acknowledges this difference in complexity for soft- and hardware. | |||

| He expects 50 pages of software documentation for each page of hardware documentation in projects with comparable budget. | |||

| \textcite{sheard_718_1998} discusses multiple points about the difference between soft- and hardware. | |||

| The point that is most applicable to this case study is that pure-hardware solution are relatively simple in their problem-space perspective. | |||

| However, the hardware solution is often complex in the solution space perspective. | |||

| The inverse is true for software. | |||

| Thus, a complex system is easier to implement with software. | |||

| \section{One-man development team} | |||

| The case study was performed by me, as a single developer. | |||

| Against all expectations, this one-man development team made the preparation phase more difficult instead of easier. | |||

| The goal of the problem description and the requirements step is to get the stakeholders on the same line \autocite{shafaat_exploring_2015}. | |||

| This involves creating agreed-upon requirements for the system, but with only one stakeholder, this agreement is implicit. | |||

| Moreover, it undermines the incentive of the problem description and requirements step. | |||

| Part of this is that there is no penalty for future reviews of the requirements, as I already agreed. | |||

| Furthermore, specific details and decisions were often made subconsciously, while I was commuting, waiting in line, or even showering. | |||

| Making structured documentation of these decisions at a later point in time without missing any of them was impossible. | |||

| The social interaction within a design team stimulates this documenting process as it improves the recall and interpretation of information. | |||

| It also improves the judgement and selection of design alternatives \autocite{lamb_221_2008}. | |||

| \section{Switching Modelling Language} | |||

| The initial idea of the development was to start with a basic model and extend that model by adding more detail. | |||

| Meaning that one design and one model would develop in parallel with each other. | |||

| However, the development of the \ac{scara} resulted in four major model versions. | |||

| The basic model started with a kinematics model. | |||

| To take the physics of the design into account, a 2D dynamics model was created. | |||

| Multiple steps of detail into the development, the 2D model was not adequate anymore. | |||

| Therefore, the design was remodeled with 3D physics. | |||

| Although this 3D physics model was able to implement the dynamic behavior, the modeling language was not suitable to design the shape of the mechanical components. | |||

| Resulting in a fourth model which represents the mechanical component design, in the form of a CAD drawing. | |||

| There are a couple of problems with this approach. | |||

| Implementing the same model with a different modelling approach, makes both models incompatible with each other. | |||

| This removes the possibility to switch back to a lower detail implementation. | |||

| Additionally, it creates the possibility to transfer parameters incorrectly from one model to another. | |||

| Such a switch is also labor intensive as the complete model has to be build from scratch again. | |||

| Furthermore, there is the possibility that this new model has been for nothing, as the planned detail proves to be unfeasible. | |||

| The point is, a future iteration of the design method must avoid these type of model switches. | |||

| \section{Reflection} | |||

| In the following section, I reflect on my own impact on the development. | |||

| The preparation and development phase are discussed separately. | |||

| \subsection{Preparation phase} | |||

| During the preparation phase often I had difficulty with getting the required information. | |||

| The information was often not specific enough or it it was overlooked. | |||

| Even though attempting to be thorough, requirements were never really specific. | |||

| As explained in the previous section, the lack of stake-holders is one of the reasons for information not being specific. | |||

| Furthermore, during the preparation information was often overlooked. | |||

| Resulting in a situation where I needed information that should have been the result of a previous step, which was not the case. | |||

| In most situations it was possible to continue with the execution of the step. | |||

| However, during the test protocol step (\autoref{sec:test_protocol}) it was not possible to continue. | |||

| Resulting in additional requirements added to the design, before continuing with the design process. | |||

| One of the main causes that attributes to the information shortage is that I am a novice designer/developer. | |||

| The experience that I have is from a graduate course and two extracurricular projects. | |||

| Being inexperienced does definitely not aid the design process. | |||

| Needless to say, more experience would improve the information situation. | |||

| However, it does not solve the problem. | |||

| Further improvements for the design method is required, to improve the information process during development. | |||

| \subsection{Development phase} | |||

| For the development phase I have significantly more experience compared to the preparation phase. | |||

| Creating models is something that I really enjoy and this improves the process significantly. | |||

| Even though the development phase went smoother than the preparation phase, there is still room for improvement. | |||

| Originally I attempted to create separate sub-models for each component. | |||

| These sub-models can then be combined into larger models. | |||

| For example, the \ac{scara} and the \ac{cdc} both include two stepper motors. | |||

| When I add detail to the stepper motor model, the \ac{scara} and the \ac{cdc} would then be updated as well. | |||

| However, each sub-model has to be updated manually. | |||

| In total four times in case of the stepper motor. | |||

| Which makes this workflow very labor intensive. | |||

| A workflow that enables easy combination and interchange of sub-models is beneficial with this design method. | |||

| It makes it easy to evaluate the latest changes, by comparing them with previous versions. | |||

| In addition, it makes it possible to lower the detail on some models during the development. | |||

| The lower detail of the sub-models can improve the simulation speed significantly. | |||

| And during the final test use the full detail to ensure that every thing is performing as expected. | |||

+ 13

- 0

content/case_evaluation_result.tex

Dosyayı Görüntüle

| @@ -0,0 +1,13 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| In the end, the development produced eight models with increasing levels of detail and one prototype. | |||

| The different levels of detail and how they are modelled are shown in \autoref{fig:levels}. | |||

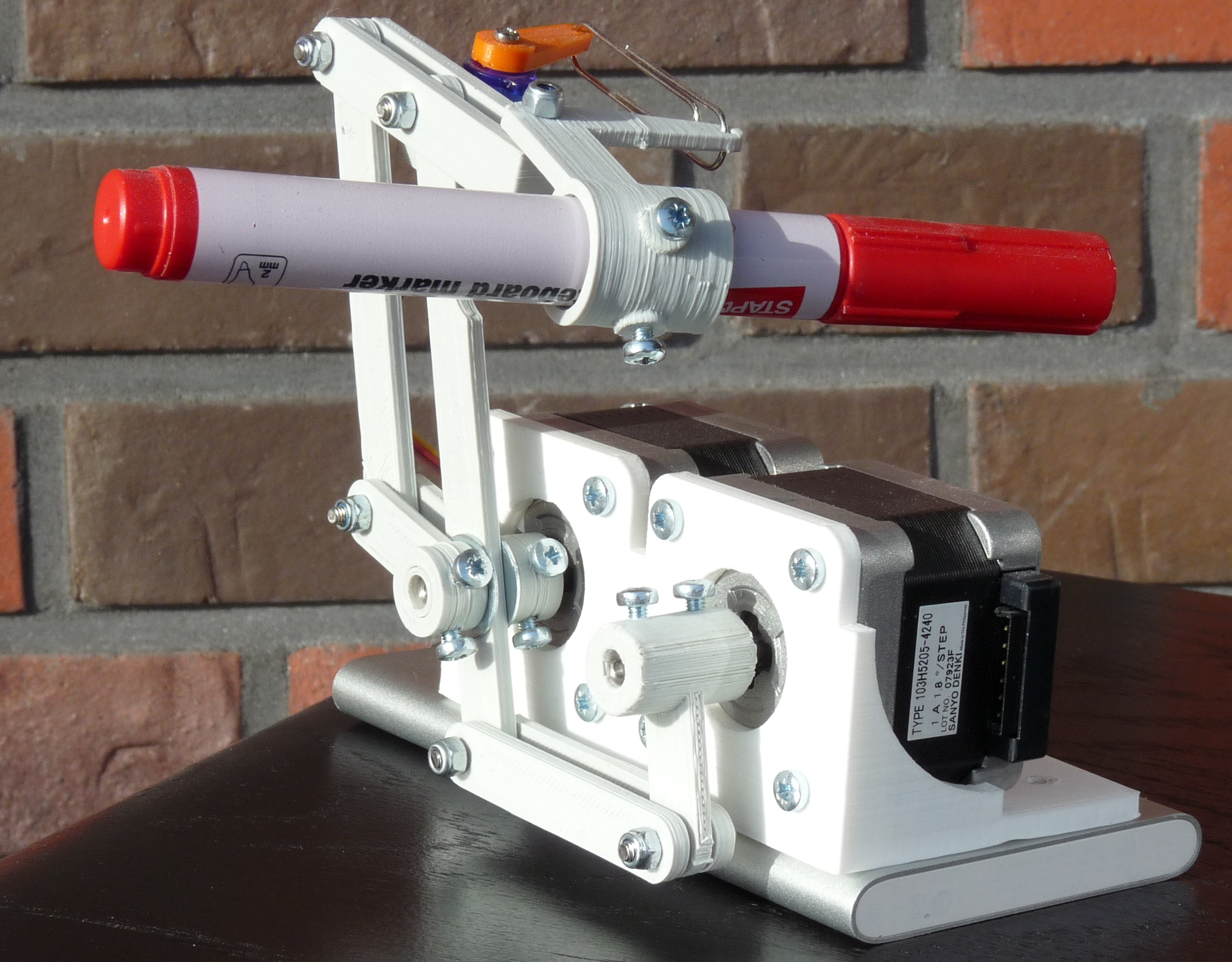

| The assembled \ac{scara} prototype is shown in \autoref{fig:prototype}. | |||

| This prototype is able execute the small rectangle as described in \autoref{test1}, and thus passes the test. | |||

| In addition, it was possible to write three characters. Therefore, passing \autoref{test_triple_char}. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \hspace{5mm} | |||

| \includegraphics[width=96mm]{graphics/prototype.JPG} | |||

| \caption{Assembled prototype of the \ac{scara}.} | |||

| \label{fig:prototype} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

+ 33

- 42

content/case_experiment_feature_definition.tex

Dosyayı Görüntüle

| @@ -1,57 +1,48 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \subsection{Feature Definition} | |||

| \label{sec:case_featuredefinition} | |||

| At this point there are specifications and an initial design for the system. | |||

| In the following steps of the design method features will be implemented one by one. | |||

| The goal of this step is to define those features. | |||

| However, the predefined approach was not able to produces a set of features that could be implemented. | |||

| This forced me to create a new approach for this step, introducing components into the design. | |||

| This section will first address why the current approach is not suitable, followed by the alternative approach. | |||

| This step divides the specifications and initial design into features. | |||

| These features will be implemented one by one during the development cycle, later in the process. | |||

| However, the initial set of features did not meet the expected set of features. | |||

| This led me to review how the features are defined. | |||

| The following sections explain what the problem caused and how it is solved. | |||

| \subsubsection{Struggles with Features} | |||

| For their case study, \textcite{broenink_rapid_2019} design a control system for a mini-segway. | |||

| This mini-segway is an already existing \ac{cps} that is used during the lab-sessions of a control course, and any control-law can be uploaded directly to the system. | |||

| The specified features of that system are defined as: | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \item Balancing the mini-segway upright | |||

| \item Steering the mini-segway | |||

| \item Driving forward and backward | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| Although this is not explicitly explained, these features have dependencies: the steering and the driving both rely on a balanced segway. | |||

| \subsubsection{Splitting the features} | |||

| The first issue was the lack of a clear border between features. | |||

| Thus, depending on where the developer places that border, the set of features changed significantly. | |||

| For example, the main functionality is \emph{writing a tweet on a white-board.} | |||

| A clear feature of this functionality is \emph{writing}. | |||

| However, must the \emph{writing} be split in a feature for writing a line, a word, or single character? | |||

| Moreover, it is also possible to argue that \emph{writing one character} a sub-feature of \emph{writing a word}, which in itself is a sub-feature of \emph{writing a line} etcetera. | |||

| A set of features for the Whiteboard writer would be: | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \item Write character on position | |||

| \item Move carriage to position | |||

| \item Write text | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| In this case, features 1 and 2 are required for feature 3. | |||

| However, in contrast with the mini-segway, the whiteboard writer does not exist yet. | |||

| Instead of creating a model based on the system, the system has to be designed first. | |||

| For these three features, the required hardware can be designed together with the feature. | |||

| The first feature would then also contain the design of the SCARA and the second feature the cable bot design. | |||

| Adding the features needed to meet the specifications for wiping the whiteboard, then such a feature would also need to design the SCARA. | |||

| In other words, more than one feature uses the SCARA in their behavior. | |||

| Resulting in the question: which feature should implement the hardware? | |||

| \subsubsection{Separating Functions and Components} | |||

| It was decided not to add the SCARA and the cable bot as features, for the reason that they do not define behavior. | |||

| Instead, the features define how the hardware behaves. | |||

| A solution to organize the relations between features and components was found in RobMoSys \autocite{noauthor_robmosys_2017}. | |||

| RobMoSys defines a separation of levels in a design. | |||

| Where the levels start functional and moves via software to hardware implementation. | |||

| Although not all levels of RobMoSys are used, it was very useful to define the features of the system. | |||

| The definition is shown in \autoref{fig:robmosys}. | |||

| The current definition of features allows to start the implementation with a component. | |||

| When the component is finished features can be implemented by following the tree upwards. | |||

| \subsubsection{Missing features} | |||

| The second issue was that the resulting set of features did not contain any of the expected features. | |||

| From the initial design it was expected that the features must include a SCARA and a cable driven carriage, because they make the system and have to be implemented somewhere in the process. | |||

| However, independent of how the functionality was split into features, no SCARA nor cable driven carriage was included in the set of features. | |||

| Which is not surprising as the SCARA and carriage do not define any functionality and can therefore not be a result from the current approach. | |||

| This mismatch between results and expectation together with the ambiguity of splitting features called for a review the design method regarding the current step. | |||

| \begin{figure*} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=0.85\linewidth]{graphics/robmosys} | |||

| \includegraphics[width=136mm]{graphics/robmosys.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Feature Definition based on the separation of levels introduced by RobMoSys} | |||

| \label{fig:robmosys} | |||

| \end{figure*} | |||

| \subsubsection{Feature and Component Hierarchy} | |||

| The solution for both issues is a hierarchical structure for the features. | |||

| The structure is based on the RobMoSys principle for separation of levels \autocite{noauthor_robmosys_2017}. | |||

| The top-level of the structure is the mission, which represents the higher level goal of the system. | |||

| Each mission consists of a number of tasks, where each task consists of a number of skills. | |||

| The levels cascade down towards the bottom-level for RobMoSys, which is the hardware layer. | |||

| Although not all the different levels from the RobMoSys principle were applicable to the design method in this study, it enabled me to create the feature definition as shown in \autoref{fig:robmosys}. | |||

| In this feature definition, the levels from mission to function are used to describe the different features of the system. | |||

| The mission describes the holistic functionality of the system. | |||

| The subsequent levels all split off in more detailed behavior. | |||

| The bottom level is used to describe the hardware components which are responsible for performing the functions of the system. | |||

| This hierarchy allows to implement features or components one by one, starting from the bottom and combining this into a system towards the top. | |||

| \subsubsection{Evaluation} | |||

| \label{sec:case_featuredefinition_evaluation} | |||

| Even though there is a feature definition that can be used in the next step, there remain a couple of difficulties. | |||

| There is still a clear separation between features and components. | |||

| And the single level of components makes it impossible to depict the dependencies between components. | |||

+ 49

- 42

content/case_experiment_test_protocol.tex

Dosyayı Görüntüle

| @@ -1,60 +1,68 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \subsection{Test Protocol} | |||

| The last step of the preparation phase is to design tests. | |||

| The tests are designed to validate if the system meets the specifications. | |||

| While defining the tests, it became clear that part of the specifications was not explicitly defined. | |||

| As the specifications were made before the design decissisions in the initial design and the feature definition, the specifications did not take that information into account. | |||

| Updating the specifications after the design decissions was overlooked during the specification of the design plan. | |||

| To ensure the repeatibility of the tests, this step starts with specifying the order of operation and improved specifications. | |||

| \label{sec:test_protocol} | |||

| The last step of the preparation phase is to implement a test protocol. | |||

| The tests are designed to validate if the system meets its requirements. | |||

| While defining the tests, it became clear that part of the requirements was not sufficiently defined. | |||

| The current requirements apply to the complete system and is not updated for the design choices made in the initial design. | |||

| If the tests are made based on the current requirements, they can only be performed when the complete design is implemented. | |||

| To create tests that apply to specific features or compoments, the requirements had to be updated. | |||

| This update adds order of operations and additional requirements and is explained in the following two sections. | |||

| The third section explains how the tests are formed based on the up-to-date requirements. | |||

| %%% Reviewed tot hier. | |||

| \subsubsection{Defining the Order of Operation} | |||

| There are two modes of operation: writing and wiping. | |||

| There are two modes of operation: writing and erasing. | |||

| Defining the order of operation also distributes the responsibility between the different components. | |||

| The writing operation can be split in the following steps: | |||

| The writing operation consists of performing the following steps: | |||

| \begin{order}{Writing} | |||

| \emph{Precondition:} Marker as end-effector. | |||

| \emph{Precondition:} Marker as tool in end-effector. | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \item Move cable driven carriage to position of characters. | |||

| \item Write three characters with the SCARA. | |||

| \item Repeat step 1 and 2 till the Tweet is on the board. | |||

| \item Move carriage away from the text on the board. | |||

| \item Move \ac{cdc} to position of characters. | |||

| \item Write three characters with the \ac{scara}. | |||

| \item Repeat step 1 and 2 untill the Tweet is on the board. | |||

| \item Move \ac{cdc} away from the text on the board. | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| \end{order} | |||

| The other operation is wiping. | |||

| This is similar to the operation of writing with the following steps: | |||

| \begin{order}{Wiping} | |||

| \emph{Precondition:} Wiper as end-effector. | |||

| The second order of operation is about the erasing. | |||

| Removing text from the board is done by the following steps: | |||

| \begin{order}{Erasing} | |||

| \emph{Precondition:} Wiper as tool in end-effector. | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \item Move cable driven carriage to position of characters. | |||

| \item Clear the area in reach of the SCARA. | |||

| \item Move \ac{cdc} to position of characters. | |||

| \item Clear the area in reach of the \ac{scara}. | |||

| \item Repeat step 1 and 2 till the Tweet is removed from on the board. | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| \end{order} | |||

| Furthermore, switching between the states requires the tool to be switched. | |||

| However, at this point, it is not known how tools will be switched. | |||

| Therefore, the order of operation is determined during the development of the end-effector. | |||

| Additionally, the missing order of operation for the end-effector did not result in difficulty while defining the tests. | |||

| \subsubsection{Improving Specifications} | |||

| Based on the order of operation, the following specifications were added to the list in \autoref{sec:specifications}: | |||

| A possible third order of operation can be defined for tool switching. | |||

| This order of operation depends on how end-effector grabs and releases the tools. | |||

| At this point, the design of the end-effector is not definitive enough to determine an order of operation. | |||

| Additionally, not having an order of operation for the end-effector did not hinder the definition of tests. | |||

| \subsubsection{Improving Requirements} | |||

| Based on the order of operations, the following requirements were added to the lists in \autoref{sec:specifications}: | |||

| \begin{specification} | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \setcounter{enumi}{12} | |||

| \input{content/input/speclistc.tex} | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| \end{specification} | |||

| These additional specifications are also based on the combined system decission that was made in section \autoref{sec:initialdesign}. | |||

| These specifications distribute responsibility between sub-components. | |||

| These additional requirements take into account that the current design consists of a \ac{scara}, end-effector and \ac{cdc}. | |||

| Where each of these components have a different role and thus a different responsibility in the system. | |||

| \subsubsection{Setting up the tests} | |||

| With the updated specifications it was possible to create a number of test cases. | |||

| In total there are five small test cases and four large test cases. | |||

| The small tests cover a sub-system and the large tests apply on the complete systems. | |||

| Each tests has a list of specifications that are covered with the test and for smaller tests the subsystem under test is also determined. | |||

| With a short description it is described how the test should be performed. | |||

| Using the updated requirements, set of test cases is created. | |||

| In total there are five small and five large test cases. | |||

| The small tests cover a single compoment or feature and the large tests combine multiple features. | |||

| Each test specifies for which requirements they apply and include a description that explains the test. | |||

| The smaller test cases also indicate on which feature or component they apply. | |||

| All ten tests are included in \autoref{app:test_specification}. | |||

| The following is a small and a large test case from these ten. | |||

| One of the small tests focusses on the speed and range requirements of the SCARA: | |||

| One of the small tests focusses on the speed and range requirements of the \ac{scara}: | |||

| \setcounter{testcounter}{0} | |||

| \begin{test}{Small rectangle} | |||

| \input{content/input/systemtest1.tex} | |||

| @@ -64,24 +72,23 @@ | |||

| \begin{test}{Repeatability} | |||

| \input{content/input/systemtest6.tex} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| The complete set of system tests is included in \autoref{app:test_specification}. | |||

| \subsubsection{Evaluation} | |||

| This step was completed without many difficulties. | |||

| Which includes the revision of the earlier specifications and definition of orders of operation. | |||

| Indicating that I overlooked details while defining the specifications in \autoref{sec:specifications}. | |||

| According to the design plan as described in \autoref{chap:analysis}, I should go back and review those specifications. | |||

| Followed by reviewing all steps after the specifications. | |||

| Which includes the revision of the earlier requirements and definition of orders of operation. | |||

| Indicating that I overlooked details while defining the requirements in \autoref{sec:specifications}. | |||

| According to the design plan as described in \autoref{chap:analysis}, I have to go back and review those requirements. | |||

| Followed by reviewing all steps after the requirements. | |||

| However, this complete review is not practical and extremely time consuming. | |||

| The point here is, looking at the evaluations of this and previous steps, that chosen design strategy is not feasible, especially as a novice designer. | |||

| In \autoref{chap:case_evaluation} I will evaluate this with more detail. | |||

| In \autoref{chap:case_evaluation} I evaluate this with more detail. | |||

| During the analysis, I expected more specific tests. | |||

| Each test could then be used as a milestone during the development of the system. | |||

| Each test can then be used as a milestone during the development of the system. | |||

| Every time detail is added, an additional test passes. | |||

| Or a test fails, notifying that something went wrong and should be investigated. | |||

| Or a test fails, notifying that something went wrong and has to be investigated. | |||

| Creating such specific tests relies on the details in the design of the system. | |||

| The current design is basic and these details are added during the feature implementation. | |||

| Nevertheless, this step resulted in a set of tests that cover all specifications and features that are specified in this preparation phase. | |||

| Nevertheless, this step resulted in a set of tests that cover all requirements and features that are specified in this preparation phase. | |||

| When all the tests pass, the system should meet all the requirements. | |||

+ 47

- 0

graphics/model_versions.tex

Dosyayı Görüntüle

| @@ -0,0 +1,47 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \documentclass{standalone} | |||

| \usepackage{tikz} | |||

| \usepackage{siltex} | |||

| \usetikzlibrary {arrows.meta,positioning,calc,math} | |||

| \tikzset{nodes={text height=.6em, text width=2.5cm, align=center, | |||

| draw=black!50, thick, font=\footnotesize, fill=white}, | |||

| >={Stealth[round,sep]}, rounded corners, semithick} | |||

| \pgfdeclarelayer{bg} | |||

| \pgfsetlayers{bg,main} | |||

| \begin{document} | |||

| \begin{tikzpicture}[y=3.5mm,x=3.2cm] | |||

| \def\rectoffset{-1.2mm,1.2mm}; | |||

| \def\rectoffsetleft{-1.9cm,0cm}; | |||

| \def\textoffset{-2.5cm,0cm}; | |||

| \def\modelgroup(#1,#2,#3){% | |||

| \begin{scope}[nodes={draw=none, fill=none,text width={},text height={}}] | |||

| \node (a) at ($(#1.north west)+(\rectoffset)+(\rectoffsetleft)$){}; | |||

| \node (b) at ($(#2.south east)-(\rectoffset)$){}; | |||

| \draw[fill=lightgray] (a) rectangle (b); | |||

| \node[anchor=center] at ($(#1)!0.5!(#2)+(\textoffset)$) {#3}; | |||

| \end{scope} | |||

| }; | |||

| \node (bm) {Basic Model}; | |||

| \node (ip)[below=1 of bm] {Ideal Physics}; | |||

| \node (dc)[below=1 of ip] {DC-motor behavior}; | |||

| \node (cl)[below=1 of dc] {Control loop}; | |||

| \node (sm)[below=1 of cl] {Stepper Motor\\ behavior}; | |||

| \node (dd)[below=1 of sm] {3D Physics}; | |||

| \node (ml)[below=1 of dd] {Marker Lifting}; | |||

| \node (cd)[below=1 of ml] {Component design}; | |||

| \path[->] (bm) edge (ip) | |||

| (ip) edge (dc) | |||

| (dc) edge (cl) | |||

| (cl) edge (sm) | |||

| (sm) edge (dd) | |||

| (dd) edge (ml) | |||

| (ml) edge (cd); | |||

| \begin{pgfonlayer}{bg} | |||

| \modelgroup(bm,bm,Kinematics); | |||

| \modelgroup(ip,sm,2D Dynamics); | |||

| \modelgroup(dd,ml,3D Dynamics); | |||

| \modelgroup(cd,cd,CAD Drawing); | |||

| \end{pgfonlayer} | |||

| \end{tikzpicture} | |||

| \end{document} | |||

BIN

graphics/prototype.JPG

Dosyayı Görüntüle

+ 40

- 0

graphics/time_table.tex

Dosyayı Görüntüle

| @@ -0,0 +1,40 @@ | |||

| \documentclass{standalone} | |||

| \usepackage{tikz,pgfplots} | |||

| \usepackage{siltex} | |||

| \usetikzlibrary{arrows.meta,positioning,calc,fadings} | |||

| \pgfplotsset{compat=1.17} | |||

| \begin{document} | |||

| \begin{tikzpicture} | |||

| \pgfmathsetlengthmacro{\xbarvalue}{-3mm} | |||

| \pgfmathsetlengthmacro{\barwidthvalue}{4mm} | |||

| \begin{axis}[ | |||

| xbar=\xbarvalue, | |||

| bar width=\barwidthvalue, | |||

| xmin=0, | |||

| xmax=21, | |||

| width=85mm, | |||

| height=75mm, | |||

| enlarge y limits=0.15, | |||

| legend style={at={(0.98,0.95)}, | |||

| anchor=north east,legend columns=-1}, | |||

| xlabel={Days}, | |||

| symbolic y coords={Software Development,Development Cycle 2,Development Cycle 1,Test Protocol,Feature Definition,Initial Design,Specifications,Problem Description}, | |||

| ytick=data, | |||

| ] | |||

| \addplot[draw=red,fill=red!40] coordinates {(2,Problem Description) (3,Specifications) (3.5,Initial Design) (13,Feature Definition) (0.5,Test Protocol) (3,Development Cycle 1) (17,Development Cycle 2) (20,Software Development)}; | |||

| \addplot[draw=blue,fill=blue!40] coordinates {(2,Problem Description) (3,Specifications) (5,Initial Design) (6,Feature Definition) (1,Test Protocol) (3,Development Cycle 1) (13,Development Cycle 2)}; | |||

| \legend{Time Spend,Time Planned}; | |||

| \pgfmathsetlengthmacro{\baroffset}{\barwidthvalue+\xbarvalue/2} | |||

| \pgfmathsetlengthmacro{\smeer}{7mm} | |||

| \node (a) at ($(axis cs:3,Development Cycle 1)-(0.1mm,0mm)+(0mm,\baroffset)$) {}; | |||

| \node (b) at ($(axis cs:3,Development Cycle 1)-(0.1mm,0mm)-(0mm,\baroffset)$) {}; | |||

| \fill[white] (a) rectangle ++(\smeer,-\barwidthvalue-1mm); | |||

| \fill[red!40,path fading=east] (b) rectangle ++(\smeer,1mm); | |||

| \fill[blue!40,path fading=east] (a) rectangle ++(\smeer,-\barwidthvalue); | |||

| \draw[white] ($(a)$) -- +(\smeer,0mm) ++(0mm,-\barwidthvalue) -- +(\smeer,0mm); | |||

| \draw[white] ($(b)$) -- +(\smeer,0mm); | |||

| \draw[blue,path fading=east] ($(a)$) -- +(\smeer,0mm) ++(0mm,-\barwidthvalue) -- +(\smeer,0mm); | |||

| \draw[red,path fading=east] ($(b)$) -- +(\smeer,0mm); | |||

| \end{axis} | |||

| \end{tikzpicture} | |||

| \end{document} | |||