3 ändrade filer med 64 tillägg och 25 borttagningar

Delad Vy

Diff Options

-

+1 -1content/appendix_test_cases.tex

-

+63 -24content/case_experiment_scara.tex

-

Binärgraphics/scara_20sim_model.png

+ 1

- 1

content/appendix_test_cases.tex

Visa fil

| @@ -2,7 +2,7 @@ | |||

| \label{app:test_specification} | |||

| \setcounter{testcounter}{0} | |||

| \begin{test}{Small rectangle} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test1}]{Small rectangle} | |||

| During this test, a rectangle will be drawn on the whiteboard using the SCARA. | |||

| This rectangle is will be at least \SI{50}{\milli\meter} high and \SI{70}{\milli\meter} wide, such that three characters fit within the rectangle. | |||

| To test the speed requirements, the rectangle should be drawn within one second. | |||

+ 63

- 24

content/case_experiment_scara.tex

Visa fil

| @@ -1,22 +1,27 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| As the previous development cycle was aborted prematurely, that cycle did not finish. | |||

| The second cycle is picks up at the feature selection step in the Development Cycle. | |||

| \subsection{Feature Selection} | |||

| The implementation of the end-effector proofed to be impractical. | |||

| This means that only two features are left. | |||

| The updated table in \autoref{tab:featurestab2} shows that the next step would be the SCARA. | |||

| The SCARA has a higher risk/time factor and covers more tests. | |||

| The updated table in \autoref{tab:featurestab2} shows the updated feature comparison. | |||

| Compared with the previous feature selection in \autoref{tab:firstfeatureselection}, the number of tests for the SCARA decreased and the Risk/Time increased. | |||

| This is because System Test \ref{test_tool_change} relied on both the SCARA and the End-effector and is no longer applicable. | |||

| Based on the feature comparison, the next component to implement is the SCARA. | |||

| \begin{table}[] | |||

| \caption{} | |||

| \label{tab:featurestab2} | |||

| \begin{tabular}{|l|l|l|l|l|l|} | |||

| \hline | |||

| Feature & Dependees & Tests & Risk & Time & Risk/Time \\ \hline | |||

| SCARA & - & 3 & 40\% & 10 days & 4 \\ \hline | |||

| End-effector & SCARA & 2 & 60\% & 8 days & 7.5 \\ \hline | |||

| SCARA & - & 2 & 50\% & 12 days & 4.2 \\ \hline | |||

| Carriage & - & 2 & 30\% & 10 days & 3 \\ \hline | |||

| \end{tabular} | |||

| \end{table} | |||

| \subsection{Rapid Development} | |||

| \subsection{Rapid Development of SCARA} | |||

| At the end of this implementation the SCARA is able to write the first characters | |||

| This will be achieved by working through different levels of detail. | |||

| Where each level adds more detail to the model. | |||

| @@ -34,7 +39,11 @@ | |||

| Together with the physics model there will be a solid 3D CAD model. | |||

| The CAD model helps to check with dimensions and possible collisions of objects. | |||

| \subsubsection{Basics} | |||

| \subsection{Variable Approach} | |||

| The following steps is to increase the detail of the model. | |||

| This is done according to the steps in the previous section. | |||

| \subsubsection{Basics implementation} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{tikzpicture} | |||

| @@ -68,29 +77,60 @@ | |||

| The second detail iteration adds the basic physics of the model. | |||

| This model was in the form of a double pendulum, with to powered joints. | |||

| The ideal motors in the joints made it that it could move with almost infinite speed. | |||

| To get a better idea of the forces in the model, the ideal motors are replaced with a beter motor model. | |||

| To get a better idea of the forces in the model, the ideal motors are replaced with a better motor model. | |||

| As the system did not operate with infinite gain anymore it the path planning was updated as well. | |||

| A simple PID controller was implemented to make SCARA follow a square path. | |||

| A simple PID-controller was implemented to make the SCARA follow a rectangular path. | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=0.9\linewidth]{graphics/scara_20sim_model.png} | |||

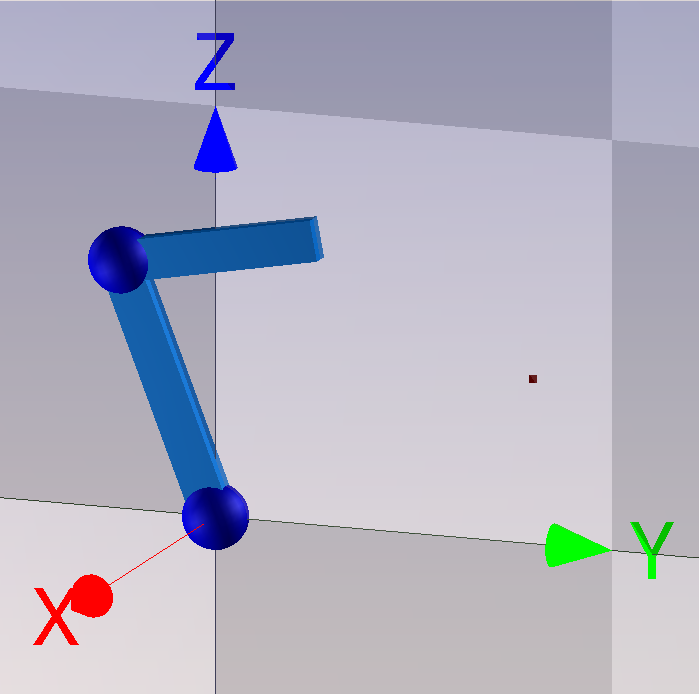

| \caption{3D plot of the current implementation. The rectangular shapes represent are the linkages and implemented as rigid bodies. | |||

| The sphere on the origin and the one between both linkages represent the actuated joints. | |||

| There is no inertia implemented for these joints.} | |||

| \label{fig:scara_20sim} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| Now that the model forms a basic with the non-ideal motors, basic physics and a controllaw, it can be used to make some estimates. | |||

| The model followed the required path in the specified amount out time. | |||

| With this, the minimum required torque could be calculated. | |||

| Which is then used to dimension the motors. | |||

| The current implementation can be seen in \autoref{fig:scara_20sim}. | |||

| Now that the model forms a basic with the non-ideal motors, basic physics and a control law, it can be used to make some estimates. | |||

| The model was configured to follow the required path in the specified amount out time according to System Test \ref{test1}. | |||

| The torque required gave a rough estimate of the required actuation force of the motors. | |||

| \subsubsection{Detailed design decisions} | |||

| The basic model gave some good insight and information about the dynamic behavior of the system. | |||

| However, the current configuration is very simple but requires a motor in the joint. | |||

| In \autoref{fig:scaradesign}, this setup is shown as configuration 1. | |||

| The disadvantage is that a motorized joint is heavy and has to be accelerated with the rest of the arm. | |||

| Other configurations in \autoref{fig:scaradesign} move the motor to a static position. | |||

| Configuration 2 is a double arm setup, but has quite limited operating range. | |||

| Due to a singularity in the system when both arms at the top are in line with each other. | |||

| Configuration 3 also has such a singularity, but due to the extended top arm this point of singularity is outside of the operating range. | |||

| However, this configuration requires one axis with two motorized joints on it. | |||

| Even though this is possible, it does increase the complexity of the construction. | |||

| By adding an extra linkage, the actuation can be split as shown in configuration 4. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=0.875\linewidth]{graphics/scara_design.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Four different SCARA configurations. The colored circles mark which of the joints are actuated. Configuration 3 has two independently actuated joints on the same position.} | |||

| \label{fig:scaradesign} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \subsubsection{Advanced Model} | |||

| The basic model contains all elementary components and detail can be added for different components. | |||

| The first step was to improve the motor models. | |||

| Up to now it was a primitive model with a source of effort, resistance and gyrator in series. | |||

| For the design it was decided to go with a stepper motor. | |||

| The advantage of a stepper motor is the holding torque, such that the motor can be forced in a certain angle. | |||

| With the new motors the controller was updated, to accommodate for the behavior of the steppers. | |||

| The actuation of the arm is done with stepper motors. | |||

| The advantage of stepper motors over simple DC-motors is that they hold a specific position. | |||

| There is no extra feedback loop required to compensate for external forces. | |||

| However, they are heavier and more expensive. | |||

| But the extra mass is probably beneficial as adds momentum to the base. | |||

| Reducing the counter movement of the base when the arm is actuated. | |||

| The next step was to upgrade the model to a full three dimensional dynamics. | |||

| Although the SCARA model itself is valid in only two dimensions, having the SCARA suspended from wires required the full dimensions. | |||

| \subsubsection{Implementing details} | |||

| The first step was to replace the DC-motor with a stepper motor model. | |||

| This based on a model by \textcite{karadeniz_modelling_2018}. | |||

| The controller is updated as well, to accommodate for the behavior of the steppers, | |||

| The next step is to implement a dynamic model of the configuration (4) as shown in \autoref{fig:scaradesign}. | |||

| The dynamics of the SCARA are based on a serial link structure \autocite{dresscher_modeling_2010}. | |||

| This allowed for a simple, yet quick implementation of the dynamics. | |||

| \subsubsection{3D modeling} | |||

| \subsubsection{3D Modeling} | |||

| With a full dynamics model in 20-sim, the next step was to design the system in OpenSCAD. | |||

| Although 20-sim has a 3D editor, it is significantly easier to build components with OpenSCAD. | |||

| Furthermore, for prototyping the OpenSCAD objects can be exported for 3D printing. | |||

| @@ -103,4 +143,3 @@ | |||

| \label{fig:scad_carriage} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \subsection{Variable Approach} | |||