Ver código fonte

Merge branch 'experiment' into 'master'

Experiment See merge request horlingsw/master-assignment-report!14merge-requests/14/merge

42 arquivos alterados com 1960 adições e 57 exclusões

Visão dividida

Opções de diferenças

-

+1 -23.gitlab-ci.yml

-

+24 -24content/analysis.tex

-

+16 -0content/appendix_specifications.tex

-

+158 -0content/appendix_test_cases.tex

-

+39 -2content/case_experiment.tex

-

+108 -0content/case_experiment_end-effector.tex

-

+60 -0content/case_experiment_feature_definition.tex

-

+193 -0content/case_experiment_initial_design.tex

-

+22 -0content/case_experiment_problem_description.tex

-

+71 -0content/case_experiment_prototype.tex

-

+95 -0content/case_experiment_recap.tex

-

+198 -0content/case_experiment_scara.tex

-

+59 -0content/case_experiment_specifications.tex

-

+87 -0content/case_experiment_test_protocol.tex

-

+2 -0content/case_method.tex

-

+8 -0content/input/speclista.tex

-

+4 -0content/input/speclistb.tex

-

+5 -0content/input/speclistc.tex

-

+19 -0content/input/systemtest1.tex

-

+18 -0content/input/systemtest6.tex

-

+55 -0graphics/cable_angle.tex

-

+24 -0graphics/cablebot.tex

-

+21 -0graphics/code_objects.tex

-

+26 -0graphics/combined.tex

-

+61 -0graphics/compare_table.tex

-

+6 -4graphics/design_flow_analysis.tex

-

+21 -0graphics/electronics.tex

-

+127 -0graphics/end-effector.tex

-

+23 -0graphics/plotter.tex

-

+22 -0graphics/polar.tex

-

+23 -0graphics/polar_protrude.tex

-

+60 -0graphics/robmosys.tex

-

BINgraphics/scad_carriage.png

-

BINgraphics/scad_scara.png

-

BINgraphics/scad_scara_circles.png

-

+32 -0graphics/scara.tex

-

BINgraphics/scara_20sim_model.png

-

+39 -0graphics/scara_arm_kinematics.tex

-

+187 -0graphics/scara_design.tex

-

+37 -0graphics/tics.tikz

-

+1 -1include

-

+8 -3report.tex

+ 1

- 23

.gitlab-ci.yml

Ver arquivo

| @@ -2,7 +2,6 @@ | |||

| --- | |||

| stages: | |||

| - typeset | |||

| - rro | |||

| variables: | |||

| GIT_SUBMODULE_STRATEGY: recursive | |||

| @@ -12,13 +11,10 @@ final_report: | |||

| image: registry.gitlab.com/silkeh/latex:latest | |||

| script: | |||

| - apk update; apk add make | |||

| - make | |||

| - mkdir tmp | |||

| - mv RichReportOutline.rro tmp/ | |||

| - make -j | |||

| artifacts: | |||

| paths: | |||

| - report.pdf | |||

| - tmp/RichReportOutline.rro | |||

| only: | |||

| refs: | |||

| - web | |||

| @@ -30,21 +26,3 @@ final_report: | |||

| - report.tex | |||

| - content/*.tex | |||

| - graphics/*.tex | |||

| rro: | |||

| stage: rro | |||

| dependencies: | |||

| - final_report | |||

| image: registry.gitlab.com/silkeh/latex:latest | |||

| script: | |||

| - latexmk -xelatex include/RichReportOutline.tex | |||

| artifacts: | |||

| paths: | |||

| - RichReportOutline.pdf | |||

| only: | |||

| refs: | |||

| - web | |||

| - branches | |||

| - tags | |||

| changes: | |||

| - tmp/RichReportOutline.rro | |||

+ 24

- 24

content/analysis.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -44,11 +44,8 @@ The steps that are introduced by \ridm are covered in more detail. | |||

| To find the best solution it is important to explore the different solutions and design space. | |||

| Often, there are many possible alternatives but they must be narrowed down to the solutions that fit within the schedule and available resources. | |||

| The best alternative is materialized in a design document together with the system requirements. | |||

| To verify that the system works in line with the system requirements, a test protocol is written for the system. | |||

| This protocol explains how the tests are preformed and what the pass conditions are. | |||

| This design document is used in the next phase of the design. | |||

| \section{Rapid Iterative Design Method} | |||

| From this point, the design plan is based on the \ridm and not anymore on the waterfall model. | |||

| The first step is the feature definition, which prepares the required features based on the initial design. | |||

| @@ -56,13 +53,20 @@ The steps that are introduced by \ridm are covered in more detail. | |||

| The definition of the feature contains a description and a set of sub-requirements which is used to implement and test the feature. | |||

| During the feature definition, the dependencies, risks and time resources are determined as well, this establishes the order of implementation in the feature selection step. | |||

| The second step is the feature selection, where one of the features is selected. | |||

| This selection is based on the dependencies, risk, and time requirements in the feature definitions. | |||

| The third step is the rapid development cycle, which uses the sub-requirements and description of the selected feature to create an initial design, a minimal implementation and tests. | |||

| In the last step, the variable detail approach is used to add detail to the minimal implementation over multiple iterations. | |||

| Based on the requirements of \ridm as explained in \autoref{chap:background}, the next step is the feature selection. | |||

| However, it became apparent that the number of tests related to a specific feature is a good metric for the selection step. | |||

| Because, at the point that a feature is implemented, the tests are completed as well, and when the tests of the complete system pass, the system meets the specifications. | |||

| Following the \ridm, these tests are specified at the start of the rapid development cycle. | |||

| This makes it impossible to use the tests during the feature selections. | |||

| Therefore, a test protocol step is added after the feature definition and before the feature selection step. | |||

| The third step is the feature selection, where one of the features is selected. | |||

| This selection is based on the dependencies, tests, risk, and time requirements in the feature definitions. | |||

| The fourth step is the rapid development cycle, which uses the sub-requirements and description of the selected feature to create an initial design and a minimal implementation. | |||

| In the last step, the variable detail approach is used to add detail to the minimal implementation over the course of multiple iterations. | |||

| The tests are used to determine if the added detail does not introduce any unexpected behavior. | |||

| This cycle of adding detail and testing is repeated till the feature is fully implemented. | |||

| From this point, the \ridm is repeated from the second step until all features are implemented. | |||

| From this point, the \ridm is repeated from the third step until all features are implemented. | |||

| \subsection{Feature Definition} | |||

| \label{sec:featuredefinition} | |||

| @@ -71,9 +75,6 @@ The steps that are introduced by \ridm are covered in more detail. | |||

| To achieve these short cycles, the features that are implemented in these cycles, are as small as possible. | |||

| However, the features must still be implemented and tested individually during the implementation and can thus not be split indefinitely. | |||

| Together with the definition of the features, the requirements are divided along the features as well. | |||

| During the initial design, a test protocol is made to evaluate the system-wide specifications. | |||

| For the feature requirements, tests are added to the test protocol as well. | |||

| These tests only require the corresponding feature to be implemented and must all pass to finish the implementation of the feature. | |||

| The optimal strategy on splitting features and specifications is strongly dependent on the type of system. | |||

| Therefore, the best engineering judgement of the developer the best tool available. | |||

| @@ -95,7 +96,14 @@ The steps that are introduced by \ridm are covered in more detail. | |||

| Due to these dependencies it is possible that the division of requirements changes, because the result of the implemented feature was not as expected. | |||

| This is not directly a problem, but a good administration of the requirements makes an update of these requirements easier. | |||

| \subsection{Test protocol} | |||

| \label{sec:systemtesting} | |||

| During the rapid development cycle and the variable detail approach, the system is tested constantly. | |||

| This is to make sure that the design still performs as expected. | |||

| The tests are based on the specifications. | |||

| Each specification must be covered with at least one test. | |||

| The tests consist of a description which specifies how to perform the test and what the result of the test must of must not be. | |||

| Together with the description, there is a list of required features to perform the test and a list of specifications that are met if the test passes. | |||

| \subsection{Feature Selection} | |||

| \label{sec:feature_selection} | |||

| @@ -194,15 +202,6 @@ The electrical motors have also internal states, but store significantly less en | |||

| An basic model would in this case only consists of the arms, possibly even without any dynamic behavior. | |||

| The dynamic behavior, motor characteristics, resistance, or gravitational force are examples of detail elements that can be added to increase the detail. | |||

| Now with initial design and the basic model, all that is left is to describe a list of tests. | |||

| The goal of these tests is to verify if the design meets the specifications of the feature. | |||

| The tests have a short description on how to perform the tests and what should be achieved. | |||

| It is important that all the specifications are covered by at least one test. | |||

| This relatively simple approach of testing is possible due to the limited scope of this thesis. | |||

| For a complexer design, the testing needs to be automated. | |||

| The \ac{amt} \autocite{jansen_automated_2019} is an interesting method to perform the testing of the models. | |||

| However, at the time of writing, the software is in a proof of concept state and not usable for this thesis. | |||

| \subsection{Variable Detail Approach} | |||

| With the variable detail approach the basic model is developed into a refined model of the feature. | |||

| This is done by implementing the detail elements over the course of multiple iterations. | |||

| @@ -233,7 +232,7 @@ The developer must evaluate if there are feasible alternatives left for this ele | |||

| When all detail elements are implemented and the basic model has evolved into a refined model of the feature, the design cycle moves back to the feature selection. | |||

| In the case that this is the last feature to implement, this concludes the development. | |||

| \section{Summation} | |||

| \section{Summary of Design Plan} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=6cm]{graphics/design_flow_analysis.pdf} | |||

| @@ -241,11 +240,12 @@ In the case that this is the last feature to implement, this concludes the devel | |||

| \label{fig:design_plan_analysis} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| The waterfall model from \ac{se} and the \ridm \autocite{broenink_rapid_2019} are combined to create the design plan as shown in \autoref{fig:design_plan_analysis}. | |||

| The first four steps of the design process form the preparation phase: problem description, specifications, initial design, and feature definition. | |||

| The first five steps of the design process form the preparation phase: problem description, specifications, initial design, feature definition, and test protocol. | |||

| The initial design step creates a holistic design based on the prior problem description and specifications step. | |||

| The last step of the preparation is the feature definition, where the initial design is split into different features. | |||

| The resulting initial design and its features together form the design proposal for the development steps. | |||

| The development step consists of the feature selection, rapid development, and variable detail steps. | |||

| The last step of the preparation phase is the test protocol step, where the tests are defined to monitor the design process and validate that the system meets the specifications. | |||

| The development cycle consists of the feature selection, rapid development, and variable detail steps. | |||

| These three steps are applied to each feature in the initial design individually. | |||

| With each iteration of the development cycle a new feature is added to the complete system. | |||

+ 16

- 0

content/appendix_specifications.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -0,0 +1,16 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \chapter{System Specifications} | |||

| \begin{specification} | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \setlength{\itemsep}{10pt} | |||

| \input{content/input/speclista.tex} | |||

| \input{content/input/speclistb.tex} | |||

| \input{content/input/speclistc.tex} | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| \end{specification} | |||

| \begin{table} | |||

| \caption{} | |||

| \label{tab:compare} | |||

| \includegraphics[width=0.8\linewidth]{graphics/compare_table.pdf} | |||

| \end{table} | |||

+ 158

- 0

content/appendix_test_cases.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -0,0 +1,158 @@ | |||

| \chapter{Test Specifications} | |||

| \label{app:test_specification} | |||

| \setcounter{testcounter}{0} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test1}]{Small rectangle} | |||

| \input{content/input/systemtest1.tex} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test_perimeter}]{Perimeter} | |||

| The Cable bot must move along the outer edges of the text area. | |||

| This area consists of three lines of text with fifty characters each. | |||

| Resulting in a perimeter of \SI{1000}{\milli\meter} wide and \SI{250}{\milli\meter} high. | |||

| This proves that reach of the system is sufficient to write the text. | |||

| Furthermore, the Cable bot should move outside of the perimeter as well. | |||

| Moving outside of the text area is to prove that Cable bot has a position where it does not obstruct the written text. | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 1, 2, 6, 11, (12) | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The Cable bot moved along the edge of the text area. | |||

| \item The Cable bot moved outside of the text area. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test_speed_carriage}]{Cable Bot Speed} | |||

| The Cable bot must be able to move a distance of \SI{80}{\milli\meter} in horizontal direction within a second. | |||

| At the start and the end of the movement the speed of the Cable bot must be zero. | |||

| This is to ensure that the SCARA can then write three characters at the given position. | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 7, 9, (12), 14, 15, 16 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item At the start and end of the test, the Cable bot does not move relative to the board. | |||

| \item During the test, the Cable bot has moved \SI{80}{\milli\meter} within \SI{1}{\second}. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test_triple_char}]{Triple Chars} | |||

| The SCARA together with the end-effector must write 3 characters without | |||

| moving the Cable bot. This extends on the small rectangle of \autoref{test1} but the | |||

| end-effector must now be able to lift the marker of the board. The three | |||

| characters should be written on the board within two seconds. | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 3, 4, (12), 13, 14 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The SCARA wrote three characters on the whiteboard within \SI{2}{\second}. | |||

| \item The Cable bot did not move more than \SI{10}{\milli\meter}. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test_tool_change}]{Tool Change} | |||

| The system has to switch in some way between the marker and a wiper, or a different color. | |||

| For this test the system must switch a tool within 10 seconds. | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector | |||

| \item[Specifications:] (5), (12), 17 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item A tool is released from the end-effector and stored for later use. | |||

| \item A different tool is attached to the end-effector. | |||

| \item The tool switch is completed within \SI{10}{\second}. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test_repeat}]{Repeatability} | |||

| \input{content/input/systemtest6.tex} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test_linear}]{Linearity} | |||

| The system must draw a grid on the drawing range (\SI{1000}{\milli\meter} x \SI{300}{\milli\meter}), with the horizontal and vertical lines spaces \SI{100}{\milli\meter} from each other. | |||

| The distance between two horizontal or two vertical lines cannot be smaller than \SI{90}{\milli\meter} or larger than \SI{110}{\milli\meter}. | |||

| The lines are not allowed to deviate more than \SI{10}{\milli\meter} in a line section of \SI{300}{\milli\meter}. | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector, Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 1, 2, 3, (12) | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item All lines are drawn, 11 vertical and 4 horizontal lines. | |||

| \item All lines in parallel separated from their neighbor by atleast \SI{90}{\milli\meter} and atmost \SI{110}{\milli\meter}. | |||

| \item Each line does not deviate more than \SI{10}{\milli\meter}. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test_writing}]{Writing} | |||

| To test the complete writing abilities the following text must be | |||

| written on the board: | |||

| \begin{verbatim} | |||

| THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG!?@,.- | |||

| 0123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282 | |||

| the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog!?@,.- | |||

| \end{verbatim} | |||

| This is a full 150 character area. It must be readable and write all the | |||

| characters correctly. It must be completed withing 150 seconds. Which is | |||

| 2 minutes and 30 seconds. | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector, Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 1, 2, 3, 4, (5), 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The text as described is readable from a atleast \SI{4}{\meter} distance. | |||

| \item The text is writen on a clean whiteboard within \SI{150}{\second}. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test_wiping}]{Wiping} | |||

| The complete board must be cleared of any marking within 60 seconds. | |||

| This is without the change of tool. | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector, Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] (5), 10, 11, 12 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The system cleaned the board within \SI{60}{\second}. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

| \begin{test}[label={test:compexity}]{Complexity} | |||

| The last test is that the design has to be complex enough. | |||

| This has to be evaluated by the developer of the system. | |||

| \tcbline | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item[Features:] SCARA, End-Effector, Cable Bot | |||

| \item[Specifications:] 8 | |||

| \item[Results:] The test passes when: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The developer can motivate that the system is complex enough to evaluate the case study. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| \end{test} | |||

+ 39

- 2

content/case_experiment.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -1,3 +1,40 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \chapter{case experiment} | |||

| \label{case_experiment} | |||

| \chapter{Case Study: Execution} | |||

| \label{chap:case_experiment} | |||

| This chapter presents the execution of the case study. | |||

| Where the goal of the case study is to evaluate the design plan as presented in \autoref{chap:analysis}. | |||

| To achieve this goal, I develop a system according to the design plan and document this design process. | |||

| As described in \autoref{sec:sod}, the system to be designed is a "Tweet on a Whiteboard Writer". | |||

| Documenting the process is done by following the evaluation protocol as described in \autoref{sec:evaluation_protocol}. | |||

| To start the case study unbiased, during the preparation I did perform as little preliminary research as possible on the design options of the whiteboard writer. | |||

| The chapter begins with the section about the preparation phase, which contains the four corresponding design steps as shown in \autoref{fig:design_plan_analysis}. | |||

| This is followed by two completed development cycles in the later two sections. | |||

| Both of these sections cover the three steps that are shown in \autoref{fig:design_plan_analysis}. | |||

| Each design step is described in a separate subsection. | |||

| Herein, the result of the design step is presented and concluded with an evaluation section at the end. | |||

| This evaluation section discusses the pairs of questions that were answered according to the evaluation protocol (\autoref{tab:prepost}). | |||

| The questions regarding the design method itself are discussed in \autoref{chap:reflection}. | |||

| \section{Preparation Phase} | |||

| The preparation phase contains four design steps. | |||

| It begins with a problem description. | |||

| This description is detailed into a list of specifications. | |||

| Based on the specifications, a number of design solutions proposed and eventually one of these solutions is chosen as initial design. | |||

| Splitting the initial design into features is done in the feature definition step. | |||

| \input{content/case_experiment_problem_description.tex} | |||

| \input{content/case_experiment_specifications.tex} | |||

| \input{content/case_experiment_initial_design.tex} | |||

| \input{content/case_experiment_feature_definition.tex} | |||

| \input{content/case_experiment_test_protocol.tex} | |||

| \section{First Development Cycle} | |||

| \input{content/case_experiment_end-effector.tex} | |||

| \section{Second Development Cycle} | |||

| \input{content/case_experiment_scara.tex} | |||

| \section{System Design Validation} | |||

| \input{content/case_experiment_prototype.tex} | |||

+ 108

- 0

content/case_experiment_end-effector.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -0,0 +1,108 @@ | |||

| With the preparation phase completed, the development cycle is next. | |||

| This consists of three steps: Feature selection, Rapid Development and Variable Approach. | |||

| The current section explains the first development cycle during the design. | |||

| For this first cycle of the design process, I design the end-effector. | |||

| However, not long after the start of the development process, the implementation proved to be too complex. | |||

| This led to the decision to abort the implemention of the end-effector. | |||

| Eventhough no progress was made, this attempted implementation did provide valuable insight in the desing process. | |||

| \subsection{Feature Selection} | |||

| \label{sec:case_feature_selection_1} | |||

| \begin{table}[] | |||

| \caption{Overview of the different features and their dependencies, number of tests that are covered and the risk/time factor. | |||

| The risk/time factor is calculate as risk divided by time.} | |||

| \label{tab:firstfeatureselection} | |||

| \begin{tabular}{|l|l|l|l|l|l|} | |||

| \hline | |||

| Feature & Dependees & Tests & Risk & Time & Risk/Time \\ \hline | |||

| \ac{scara} & - & 3 & 40\% & 10 days & 4 \\ \hline | |||

| End-effector & \ac{scara} & 2 & 60\% & 8 days & 7.5 \\ \hline | |||

| \ac{cdc} & - & 2 & 30\% & 10 days & 3 \\ \hline | |||

| \end{tabular} | |||

| \end{table} | |||

| For each feature in the system the dependees, tests and risk/time factor is determined, as explained in \autoref{sec:feature_selection}. | |||

| These values are combined into \autoref{tab:firstfeatureselection}. | |||

| The \ac{scara} depends on the end-effector, as explained in the initial design. | |||

| However, for the \ac{cdc} no dependency was defined even though it has to lift the other two components. | |||

| This is mainly because the torque and range requirements of the \ac{scara} depending on the implementation of the end-effector. | |||

| Especially the required range depends on the method of grabbing and releasing tools. | |||

| For the \ac{cdc} it only changes the mass that has to be lifted. | |||

| Upgrading the motor torque is a minor parametric change and the dependency is therefore insignificant. | |||

| The testing number is directly the number of tests that apply to that feature. | |||

| The risk and time values are not determined with a specific protocol, but with simple engineering judgement. | |||

| The estimated risk is high for the end-effector due to the collision dynamics of the operation. | |||

| It has to grab something and that is difficult to model. Furthermore, it was not known if that design would work. | |||

| The \ac{scara} has the most moving parts, but no difficult dynamics and has therefore an estimated risk of medium. | |||

| For the \ac{cdc} there was no real risks and got therefore a low risk indication. | |||

| Based on \autoref{tab:firstfeatureselection}, the end-effector is implemented first. | |||

| The end-effector has the most dependees, and is therefore chosen above the other two. | |||

| \subsubsection{Evaluation} | |||

| This first step of the detail design phase did go well. | |||

| Although risk and time assessment is always depend on some engineering judgment, this human factor introduces uncertainty in the assessment. | |||

| However, an improved approach for the risk assesment can drastically reduce this human factor. | |||

| Within a design team a form of planning poker \autocite{grenning_planning_2002} could be a good option. | |||

| \subsection{Rapid Development of the End-Effector} | |||

| This section explains the process of the development of the end-effector. | |||

| The first step is to create an initial design of the model. | |||

| In subsequent steps, detail is added to this model. | |||

| The previous section explained the relative high risk assessment for the end-effector. | |||

| Which was not exaggerated as the implementation proved to be troublesome. | |||

| Eventually, the implementation was unfeasible and was therefore cut short. | |||

| Nonetheless did it result in useful evaluation points on the design method. | |||

| The process of this step is explained in the following sections. | |||

| The development starts with an initial design of the system. | |||

| The next step is to develop that further into a model and prototype. | |||

| This development did not get past the basic model implementation due to unforeseen difficulties. | |||

| However, the evaluation gave new useful insight on the design plan. | |||

| \subsubsection{Initial design} | |||

| The end-effector is mounted on the \ac{scara} and acts as an interface. | |||

| With the end-effector, the \ac{scara} is able to grab and release tools. | |||

| There are multiple approaches to handle these tools. | |||

| However, there is a trade-off to be made with the \ac{scara} feature, the heavier the end-effector is, the more force the \ac{scara} must deliver. | |||

| And because the goal is to make the \ac{scara} light and quick, this end-effector must be light-weight as well. | |||

| The best options in this case is a simple spring-loaded clamp. | |||

| To release the tool, the clamp is forced open, pushing it against the holder. | |||

| As the end-effector is connected to the \ac{scara}, the \ac{scara} is responsible for the pushing force. | |||

| Because the actuation force of the \ac{scara} is used, it removes the need for an additional servo in the end-effector. | |||

| Resulting in a simpler and lighter design. | |||

| The initial design of the clamp and the operation is shown in \autoref{fig:gripper}. | |||

| Although this design requires the \ac{scara} to deliver more force. | |||

| The relative low mass of the end-effector also keeps the moment of inertia small. | |||

| Therefore, the current design reduces the impact on the acceleration of the \ac{scara} to a minimum. | |||

| \begin{figure*} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=151mm]{graphics/end-effector.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Operation of the end-effector. The clamp is forced open against the holder to release the marker. | |||

| Instead of releasing, the marker is grabbed by reversing the order of executing for these steps.} | |||

| \label{fig:gripper} | |||

| \end{figure*} | |||

| \subsubsection{Behavior Modelling} | |||

| The next step is to implement this design with the corresponding behavior in a dynamic model. | |||

| The challenge in this case is the modelling of the contact dynamics. | |||

| Based on some experience in modelling with collisions, I decided to use the 20-sim 3D mechanics editor. | |||

| Unfortunately, there is little tooling available and there are no debugging options if the model does not behave as expected. | |||

| The marker kept falling trough the gripper or flew away. | |||

| With the small amount of progress made in two days the implementation was not promising. | |||

| A system freeze caused the model to corrupt, where the complete configuration of the shapes and their collisions was lost. | |||

| Based on the loss of work and the low feasibility of the implementation, the decision was made to remove the end-effector from the design. | |||

| With the end-effector removed, the \ac{scara} gets a direct connection with the marker. | |||

| The lifting of the marker from the is included in the \ac{scara} as well. | |||

| Furthermore, this means that the erasing is no longer possible as a feature. | |||

| \subsubsection{Evaluation} | |||

| The lost progress of the model is unfortunate, but the implementation did not go as expected anyway. | |||

| It was probably for the best as it forced an evaluation of the design and avoided a tunnel vision while trying to get it to work. | |||

| However, it did show the value of the risk/time analysis. | |||

| This early failure resulted in changes for other components. | |||

| But as none of the components were implemented yet, no work was lost. | |||

+ 60

- 0

content/case_experiment_feature_definition.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -0,0 +1,60 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \subsection{Feature Definition} | |||

| \label{sec:case_featuredefinition} | |||

| At this point there are specifications and an initial design for the system. | |||

| In the following steps of the design method features will be implemented one by one. | |||

| The goal of this step is to define those features. | |||

| However, the predefined approach was not able to produces a set of features that could be implemented. | |||

| This forced me to create a new approach for this step, introducing components into the design. | |||

| This section will first address why the current approach is not suitable, followed by the alternative approach. | |||

| \subsubsection{Struggles with Features} | |||

| For their case study, \textcite{broenink_rapid_2019} design a control system for a mini-segway. | |||

| This mini-segway is an already existing \ac{cps} that is used during the lab-sessions of a control course, and any control-law can be uploaded directly to the system. | |||

| The specified features of that system are defined as: | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \item Balancing the mini-segway upright | |||

| \item Steering the mini-segway | |||

| \item Driving forward and backward | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| Although this is not explicitly explained, these features have dependencies: the steering and the driving both rely on a balanced segway. | |||

| A set of features for the Whiteboard writer would be: | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \item Write character on position | |||

| \item Move carriage to position | |||

| \item Write text | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| In this case, features 1 and 2 are required for feature 3. | |||

| However, in contrast with the mini-segway, the whiteboard writer does not exist yet. | |||

| Instead of creating a model based on the system, the system has to be designed first. | |||

| For these three features, the required hardware can be designed together with the feature. | |||

| The first feature would then also contain the design of the SCARA and the second feature the cable bot design. | |||

| Adding the features needed to meet the specifications for wiping the whiteboard, then such a feature would also need to design the SCARA. | |||

| In other words, more than one feature uses the SCARA in their behavior. | |||

| Resulting in the question: which feature should implement the hardware? | |||

| \subsubsection{Separating Functions and Components} | |||

| It was decided not to add the SCARA and the cable bot as features, for the reason that they do not define behavior. | |||

| Instead, the features define how the hardware behaves. | |||

| A solution to organize the relations between features and components was found in RobMoSys \autocite{noauthor_robmosys_2017}. | |||

| RobMoSys defines a separation of levels in a design. | |||

| Where the levels start functional and moves via software to hardware implementation. | |||

| Although not all levels of RobMoSys are used, it was very useful to define the features of the system. | |||

| The definition is shown in \autoref{fig:robmosys}. | |||

| The current definition of features allows to start the implementation with a component. | |||

| When the component is finished features can be implemented by following the tree upwards. | |||

| \begin{figure*} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=0.85\linewidth]{graphics/robmosys} | |||

| \caption{Feature Definition based on the separation of levels introduced by RobMoSys} | |||

| \label{fig:robmosys} | |||

| \end{figure*} | |||

| \subsubsection{Evaluation} | |||

| Even though there is a feature definition that can be used in the next step, there remain a couple of difficulties. | |||

| There is still a clear separation between features and components. | |||

| And the single level of components makes it impossible to depict the dependencies between components. | |||

| Developing larger and complex systems will have sub-components in the system, introducing even more dependencies. | |||

| Therefore, this is not a valid solution for feature definition. | |||

| Fortunately the current solution suffices to continue the case study. | |||

+ 193

- 0

content/case_experiment_initial_design.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -0,0 +1,193 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \subsection{Initial design} | |||

| \label{sec:initialdesign} | |||

| The initial design started with a design space exploration. | |||

| The goal was to collect possible solutions and ideas for the implementation. | |||

| The exploration resulted in a lot of whiteboard writing robots ideas. | |||

| These robots can be sorted in four different configurations | |||

| Each configuration explained in the following sections. | |||

| From the possible configurations, the one that fits the specifications best, is made into an initial design. | |||

| \subsubsection{Cable-Driven} | |||

| The cable-driven robot is suspended with multiple cables. | |||

| The end-effector that contains the marker is moved along a board by changing the length of the cables. | |||

| The cable-based positioning systems result in an end-effector with a large range and high velocities. | |||

| A basic setup can be seen in \autoref{fig:cablebotdrawing}. | |||

| This given setup contains two cables that are motorized. | |||

| The big advantage of this system is that it scales well, as the cables can have almost any length. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=10.8cm]{graphics/cablebot.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Planar view of cable driven robot. This setup contains two motorized pulleys in both top corners. From these two cables a mass is suspended at position $x,y$. | |||

| By changing the length of the cables, the mass can be moved over along the whole board.} | |||

| \label{fig:cablebotdrawing} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=3.74cm]{graphics/cable_angle.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Illustrating the limit for pure horizontal acceleration $a$, for different angles to compensate for gravitational acceleration $g$. | |||

| The red arrow represents the acceleration as a result of the pulling force of the cable, which is vectorized in a vertical acceleration that compensates $g$ and a vertical acceleration $a$.} | |||

| \label{fig:cable_angle} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| Although it is possible to achieve high velocities, this system is limited by the gravitational acceleration. | |||

| In case of vertical acceleration, the maximum downward acceleration or upward deceleration is limited by \SI{9.81}{\meter\per\second\squared}. | |||

| The horizontal acceleration depends on the relative angle of the suspending cable. | |||

| The closer the end-effector is below the cable pulley, the lower the pure horizontal acceleration becomes. | |||

| \autoref{fig:cable_angle} illustrates the horizontal acceleration for different angles. | |||

| A possible solution to this is to add one or two additional wires to the system. | |||

| These can pull on the system to 'assist' the gravitational force. | |||

| Depending on the implementation, the extra cables make the system over-constrained. | |||

| Nevertheless, the extra cables allow for higher acceleration limits in vertical and horizontal direction. | |||

| \subsubsection{Cartesian-coordinate robot} | |||

| This configuration is a very common design for plotters and shown in \autoref{fig:plotter}. | |||

| This setup is also known as a gantry robot or linear robot. | |||

| It normally consists of two sliders, which behave as a prismatic joint. | |||

| Because each slider covers a single X or Y axis, the control and dynamics of this system are rather simple. | |||

| The biggest challenge is in the construction of the system, especially when the size of the system is increased. | |||

| The larger system requires bigger length sliders, which are expensive. | |||

| Another difficulty is the actuation of both horizontal sliders, if these sliders do not operate synchronous, the vertical slider rotates. | |||

| However, the construction of the slider is not able to rotate, resulting in damage to the system. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=8.74cm]{graphics/plotter.pdf} | |||

| \caption{This Cartesian plotter consists of two horizontal sliders to provide the $x$-movement and one vertical slider to provide the $y$-movement.} | |||

| \label{fig:plotter} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \subsubsection{Polar-coordinate robot} | |||

| This robot is a combination of a prismatic and a revolute joint. | |||

| Where the revolute joint can rotate the prismatic joint as seen in \autoref{fig:polar}. | |||

| With this it can reach any point within a radius from the rotational joint. | |||

| This is a little more complex design than the Cartesian robot. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=8.74cm]{graphics/polar.pdf} | |||

| \caption{A combination of a revolute joint and a prismatic joint, creating a polar-coordinate robot.} | |||

| \label{fig:polar} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=3.74cm]{graphics/polar_protrude.pdf} | |||

| \caption{The diagonal lined section shows the part of the protruding area that is used by the arm.} | |||

| \label{fig:polar_protrude} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| This robot has multiple disadvantages. | |||

| The range of the robot is defined by the length of the prismatic joint. | |||

| Thus when the operating range is doubled, the robot size has to be doubled or even more than that. | |||

| Furthermore, when the arm of the robot is retracted, it protrudes on the other side. | |||

| Therefore, the complete radius around the revolute joint cannot have any obstacles. | |||

| \autoref{fig:polar_protrude} gives an impression of the required area. | |||

| Even with this area, the arm cannot reach the complete board. | |||

| This makes required space of the setup very inefficient. | |||

| Another disadvantage is that a long arm increases the moment of inertia and the gravitational torque on the joint quadratically. | |||

| Furthermore, the long arm introduces stiffness problems and it amplifies any inaccuracy in the joint. | |||

| \subsubsection{SCARA} | |||

| The SCARA robot is a configuration with two linkages that are connected via rotational joints. | |||

| It can be compared to a human arm drawing on a table as seen in \autoref{fig:scara}. | |||

| Similar to the Polar robot it can reach all points within a radius from the base of the robot. | |||

| But the SCARA does not protrude like the polar arm (\autoref{fig:polar_protrude}). | |||

| Depending on the configuration of the arm, it is possible to keep the arm completely within the area of operation. | |||

| A downside is that the mass of the additional joint and extra arm length increase the moment of inertia and gravitational torque similar to the polar robot. | |||

| This makes the SCARA configuration convenient for small working areas as that keeps the forces managable. | |||

| Additionally, as the arms of the SCARA have a fixed length, it is possible to create a counter balance. | |||

| This can be used to remove any gravitational torque from the system. It would however increase the moment of inertia even further. | |||

| For current specifications, the working area is too large for any practical application of the SCARA. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=8.74cm]{graphics/scara.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Schematic example of a SCARA, consisting of two rotation linkages. This setup can be compared to a human arm, where the gray base above the whiteboard represents the shoulder and the connections between both linkages the elbow.} | |||

| \label{fig:scara} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \subsubsection{Choice of system} | |||

| The previous sections have shown four different configurations. | |||

| These configurations are compared in \autoref{tab:initial_design}. | |||

| Each of the systems are scored on range, speed, cost, obstruction, effective area, and the interesting dynamics: | |||

| \begin{description} | |||

| \item{\emph{Range}}\\ | |||

| The range scores the system on the practical dimension of the system, larger is better. | |||

| The cable and cartesian configuration scale very well, the cables or slider rails can be made longer without real difficulty. | |||

| The SCARA or polar configuration run into problems with the arm lengths, as forces scale quadratically with their length. | |||

| \item{\emph{Speed}}\\ | |||

| Except for the cable bot, all configurations score sufficient on speed. | |||

| The cable bot can reach high velocities, but the acceleration is limited, depending on the configuration, to the gravitational acceleration. | |||

| \item{\emph{Cost}}\\ | |||

| For the cost, all systems fit within the €200 budget, except for the Cartesian setup. | |||

| All systems require DC or stepper motors, but the cartesian setup also requires linear sliders which are expensive, especially for longer distances. | |||

| \item{\emph{Obstruction}}\\ | |||

| The obstruction score depends on the capability of the system to move away from the text on the board, such that the system does not obstruct the written tweet. | |||

| All systems except for the cable bot can move themself outside of the working area. | |||

| It is possible that the cables of the cable bot obstruct the view. | |||

| However, the wires are expected to be thin enough to not block any text. | |||

| \item{\emph{Scalability}}\\ | |||

| For the scalability, only the cable bot scores high. | |||

| The cables make it possible to easily change the operating range of the system, only requiring reconfiguration. | |||

| The cartesian system scales poor because the length of the sliders is fixed, and longer sliders are expensive. | |||

| For the Polar system and SCARA, the forces on the joints scale quadratically with the length of the arms. | |||

| However, the SCARA can be build with counter balance making it scale less worse than the Polar system. | |||

| \item{\emph{Effective Area}}\\ | |||

| With the effective area, the system is scored on the area it requires to operated versus the writable area. | |||

| \item{\emph{Interesting Dynamics}}\\ | |||

| The last metric, scores the system on the complexity of the dynamics. | |||

| This is a more subjective metric, but also a very important one. | |||

| In the problem description, the complexity of the dynamics was determined as one of the core requirements. | |||

| The cartesian configuration is trivial, both sliders operate completely separate from each other and the position coordinates can be mapped one to one with the sliders. | |||

| For the other configuration, some inverse kinematics are required to get from desired position to the control angles of the system. | |||

| \end{description} | |||

| \begin{table}[] | |||

| \caption{Table with comparison of the four proposed configurations and a combined configuration of the cable bot and the SCARA.} | |||

| \label{tab:initial_design} | |||

| \begin{tabular}{l|l|l|l|l|l|} | |||

| \cline{2-6} | |||

| & Cable bot & Cartesian & Polar & SCARA & Combined \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Range} & + + & + & - - & - & + + \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Speed} & - & + & + & + + & + \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Cost} & + + & - - & + & + & + \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Obstruction} & - & + & + & + & - \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Scalability} & + + & - & - - & - & + \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{\begin{tabular}[c]{@{}l@{}}Effective\\ area\end{tabular}} & + + & + & - - & + & + + \\ \hline | |||

| \multicolumn{1}{|l|}{\begin{tabular}[c]{@{}l@{}}Interesting\\ dynamics\end{tabular}} & - & - - & - & + & + + \\ \hline | |||

| \end{tabular} | |||

| \end{table} | |||

| Based on this comparison, I disqualified the cartesian and polar system. | |||

| The cartesian has no interesting dynamics and is expensive to build at the current scale. | |||

| The polar system is just not feasible, the arm length required to cover the writing area results forces that are too large. | |||

| Making a rotational joint that delivers the torque and velocity required for such an arm, is just out of the scope of this case study. | |||

| The two remaining configurations come with serious downsides as well. | |||

| The cable bot is slow, and the arm length for the SCARA is also likely to cause problems. | |||

| However, by combining both, it is possible to get a system that fits the requirements very well. | |||

| By building a small SCARA that is the suspended by the cable bot, it combines the best of both worlds. | |||

| The small SCARA is quick and accurate, while the cable bot gives the system an enormous range. | |||

| Resulting in a system that scores high on all criteria except obstruction. | |||

| The grading for the combined system is shown in the most right column in \autoref{tab:initial_design}. | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=10.8cm]{graphics/combined.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Combined system that integrates the cable bot together with the SCARA. The SCARA in red is mounted on the carriage. This carriage is then suspended by cables.} | |||

| \label{fig:combined} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| In the combined system, the SCARA will only be large enough to write a small number of characters at the time. | |||

| This will alternate with the cable bot moving the base of the SCARA to the next position, so that it can write the next set of characters on the whiteboard. | |||

| \autoref{fig:combined} shows a simple view of the system. | |||

| \subsubsection{Evaluation} | |||

| This was the first step that felt really productive in the design process. | |||

| It created a enormous amount of information and insight of the design. | |||

| In hind sight, it would have been useful to have this information during the specifications step. | |||

| However, as the specifications step are mainly on the "what" to solve, and specifically not on "how" to solve it, this information was avoided on purpose during the specifications step. | |||

| This step did result in an initial design that can be used in the next steps. | |||

| However, I noticed that none of the previous steps have a clear start or end. | |||

| For the problem description and the specification steps the question is when all required information is collected. | |||

| In the initial design it is always possible continue researching design options to come up with an even better design. | |||

| Especially with complex system, it is unrealistic to create complete specifications before making design decissions. | |||

| Resulting in the question: at what point do we have enough information and must we move to the next design step? | |||

| This is also known as the \emph{requirement versus design paradox} \autocite{fitzgerald_collaborative_2014}. | |||

+ 22

- 0

content/case_experiment_problem_description.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -0,0 +1,22 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \subsection{Problem Description} | |||

| The problem description describes the need for a solution or system. | |||

| In this case, I want a robot that can write a tweet on a whiteboard. | |||

| A specific requirement is that the system must be complex enough, such that it uses sufficient aspects of the design method to be able to evaluate that design method. | |||

| The system must meet the following requirements: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item Write a twitter message, or tweet, on a whiteboard. | |||

| \item Remove the tweet from the whiteboard. | |||

| \item Write the tweet within three minutes on the board. | |||

| \item The text must be readable across a meeting room. | |||

| \item The solution must contain interesting dynamics. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| \subsubsection{Evaluation} | |||

| The problem description is very brief, which is not a complete surprise. | |||

| As most of the work for the problem description was already done by choosing the subject of design. | |||

| However, it was not expected to be this minimal. | |||

| Perhaps the most serious disadvantage is the absence of stakeholders. | |||

| Normally, a good problem definition focusses on getting the stakeholders on the same line \autocite{shafaat_exploring_2015}. | |||

| However, this case study does only have one stakeholder, the author, defeating the purpose getting everyone on the same line. | |||

| Creating a more elaborate problem description would not improve the evaluation of the design process, but it does cost valuable time. | |||

+ 71

- 0

content/case_experiment_prototype.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -0,0 +1,71 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| To validate the dynamical and mechanical models, I will build a prototype of the current design. | |||

| For the mechanical design, the CAD model is used to print the custom parts. | |||

| Other components, such as steppers, microcontroller, screws and miscellaneous electronics, are ordered. | |||

| To test the dynamics, the steppers and servo have to be actuated. | |||

| To achieve this actuation a control law is written in software. | |||

| \subsection{Mechanical Construction} | |||

| With the 3D printed parts the SCARA was easy to construct. | |||

| The diameter of the holes in the parts were printed slightly undersized. | |||

| This was on purpose, such that the holes can be drilled to the specified size. | |||

| To connect the bodies on the joints, a bolt with washers is used. | |||

| Although this is clearly not the ideal technique to build joints, it was by far the easiest option. | |||

| During assembly I noticed that the bolts of a joint and those that hold the stepper motor in place collided. | |||

| This was possible because the bolts were not included in the CAD-model. | |||

| In hindsight this should have been included. | |||

| Fortunately there was enough clearance to mount the SCARA slightly further on the axle. | |||

| Resulting in an operating SCARA without having to redesign the mechanics. | |||

| \subsection{Control of the SCARA} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=5cm]{graphics/electronics.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Hardware connections. The servo motor connected to a pwm-output. The stepper controller connected via UART and IO-pins. The stepper controller provides the correct current for the stepper motors.} | |||

| \label{fig:signals} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| Although the focus of the design plan was specifically not the software, it still forms a important part of the development. | |||

| To run the hardware, I chose for for a STM32 \ac{mcu}. This is a powerfull processor with sufficient IO available. | |||

| The servo motor is directly connected to the IO of the \ac{mcu} while the stepper motor is connected via a stepper controller board, see \autoref{fig:signals}. | |||

| RIOT-OS was chosen as an operating system due to prior experience and available support. | |||

| To be able to write characters on the board the following tasks have to be implemented in software: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item Driver for the stepper controller | |||

| \item Driver for servo motor | |||

| \item Inverse Kinematics | |||

| \item Control/Path planning | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| The stepper controller chip can be configured over UART and has two simple IO pins for step and direction signal. | |||

| To simplify the control, the software driver configures the stepper controller and includes functions to move the stepper motor to a certain angle. | |||

| Meaning that the feedforward control of the steppers is handled by the software driver class. | |||

| The angle of the servo motor is controlled by the pulse length of a square wave. | |||

| This signal is generated in the IO peripherals as a PWM signal. | |||

| The software driver has a toggle function that changes the pulse length. Making the maker lift from or lower on the board. | |||

| The code for the servo driver was already available as a module in RIOT-OS. | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=2.83cm]{graphics/code_objects.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Simplified data flow in the software. The path planning generates a vector to the next set point. The interpolation reduces the length of this vector. With the inverse kinematics the required stepper motor angles are generated. These angles are set as new set point for the stepper driver.} | |||

| \label{fig:objects} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| The path planning is able to write three characters with the SCARA. | |||

| The font for the characters is made by \textcite{hudson_asteroids_2015}. | |||

| This font consists of a simple coordinates for characters and is written in C. | |||

| The path planning is updated with a fixed interval. | |||

| During the update, the set point is linearly interpolated, otherwise the lines are curved between set points. | |||

| To get the angle set points for the stepper motors, the $x,y$-coordinate set point is converted using the inverse kinematics. | |||

| The inverse kinematics is analogous to the model that is used in the development cycle of the SCARA. | |||

| The angle set points are updated for the stepper driver. | |||

| The data path is shown in \autoref{fig:objects}. | |||

| The stepper driver has a feedforward controller. | |||

| The driver limits the acceleration and speed to keep the motor within operating specifications and keeps track of the current status of the stepper motor. | |||

| When the angle set point is updated, the driver calculates the time interval between each step and sets a hardware timer to that interval. | |||

| This allows the controller and other drivers to be executed between each step. | |||

| This approach works only if the code executes fast enough. | |||

| During the testing, I found that the inverse kinematics calculation was too expensive, even with the integrated floating point unit. | |||

| As the \ac{mcu} has sufficient flash storage available, the inverse kinematics calculation is replaced by a lookup table. | |||

+ 95

- 0

content/case_experiment_recap.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -0,0 +1,95 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| \subsection{Recap} | |||

| During the problem definition and the specifications step it was difficult to stay within the "what" has to be solved and not go into the "how" it has to be solved. | |||

| Furthermore, the test definitions of the last step conclude the preliminary design phase. | |||

| This preliminary design shows a clear notion of a hasty execution from a design standpoint. | |||

| The preliminary design was performed over a period of 5 weeks, by one developer with little experience in design documentation. | |||

| This makes notion of hasty not surprising for this unproven design method. | |||

| That does not mean that this preliminary design is a waste of time. | |||

| From the evaluation moments during the preliminary phase there are a couple of interesting points. | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item The lack of a design team with experienced engineers would drastically improve the execution of this design phase. | |||

| Such a team is also able to find the smaller problems of such a design phase, which are currently completely overlooked. | |||

| \item It is not possible to view each step in the design process as singular. | |||

| Each step creates more insight and information about the final design. | |||

| Making a very strong separation between the steps forces the developer to make decisions on to little information. | |||

| \item The term features has to be split in to functions and components for a hardware design. | |||

| The actual implementation are the components such that they can perform the function. | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| Another point was noticed while evaluation the complete preliminary design phase. | |||

| The lack of a team makes it easy to forget documenting intuitive design decisions. | |||

| Although the design method is followed as closely as possible, it often occurs that a decision is made outside of the working environment. | |||

| This was noticed during the writing of this chapter that some design decisions were completely missing. | |||

| However, during the next phase, these decisions do play a crucial role. | |||

| Therefore, this section will give a short recap of the planned design. | |||

| \subsubsection{Complete system} | |||

| From the initial design the abstract shape of the design is clear. | |||

| This is still in line with \autoref{fig:general_design}. | |||

| The SCARA is small and can therefore move the arm quick with a fine precision. | |||

| At the end of the SCARA there is a end-effector that can grab, hold, end release tool. | |||

| It holds a marker while writing and with help of the SCARA it can release the marker. | |||

| Then it can grab a cleaning tool to erase whiteboard. | |||

| To compensate for the small reach of the SCARA, the SCARA will be mounted to a carriage. | |||

| This carriage is suspended from cables and can move along the whiteboard. | |||

| The cables give the system a enormous range and velocity. | |||

| However, it is not very good in acceleration as cables cannot push. | |||

| This makes it suitable for the large and course movements along the board, which complements the movement characteristics of the SCARA. | |||

| \subsubsection{SCARA} | |||

| The central component of the system is the SCARA. | |||

| There are a couple of design options for the SCARA. | |||

| As the dynamic complexity is a important part of this design, there will be two arms. | |||

| There are some different options for the configuration of the arms and their actuation. | |||

| \autoref{fig:configurations} shows four of the possible configurations that are considered during the design phase. | |||

| There are still options about where to place the motors and how to connect the joints. | |||

| \rrot{Figure needs some graphic improvement} | |||

| %\begin{figure} | |||

| % \centering | |||

| % \includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{graphics/IMG_20201001_134140.jpg} | |||

| % \caption{Four different SCARA configurations} | |||

| % \label{fig:configurations} | |||

| %\end{figure} | |||

| \subsubsection{End-effector} | |||

| The end-effector is the connection between the SCARA and the tool. | |||

| It has two main functions: lifting the tool from the board and switching the tool. | |||

| The tool switching functionality is performed by the SCARA as well, by moving the end-effector to the right position. | |||

| However, the role of the SCARA is strongly dependent\footnote{ Note, that this dependency exists but not represented in \autoref{fig:robmosys} due to the limitation of the current method.} on how the end-effector is implemented. | |||

| For the grabbing function there is a configuration that uses a spring-loaded clamp. | |||

| Where one side of the clamp is longer so it can be opened by moving the SCARA. | |||

| This operation is shown in \autoref{fig:gripper} | |||

| %\begin{figure*} | |||

| % \centering | |||

| % \includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{graphics/IMG_20201001_144018.jpg} | |||

| % \caption{Operation principle of a spring-loaded tool clamp showed from left to right. The green circle represents the tool and the red arm a tool holder. The solid ground is what pushed the upper arm open so the marker can be placed in the tool holder.} | |||

| % \label{fig:gripper} | |||

| %\end{figure*} | |||

| Another dynamically simpler option is to open the clamp with a motor. | |||

| The motor adds weight to the end-effector which might require the SCARA to operate slower or to be build stronger. | |||

| This component is probably the most difficult one because it requires clamping of the tools. | |||

| Modeling this behavior is difficult as it will involve contact dynamics. | |||

| \subsubsection{Cable driven Carriage} | |||

| The end-effector and the SCARA are moved all together on a carriage. | |||

| The carriage will be suspended from two or four cables. | |||

| A configuration with two cables is the simplest. | |||

| However, the tension in this system is generated by the gravitational pull. | |||

| This introduces limitations in the acceleration of the system. | |||

| If the carriage moves upwards and the cable pulleys stop. | |||

| The carriage is only decelerated by the force of gravity. | |||

| Moving over its set point, followed by crashing down in to the cables. | |||

| However, making the system with four motorized pulleys makes the system over constrained. | |||

| This will solve the acceleration problem. But it will create a difficult positioning system. | |||

| As all the wires have to be tensioned but not distort the movement by restricting the other motors. | |||

| \subsubsection{Electronics} | |||

| Although this mainly is a hardware design, there is going to be some control-software. | |||

| For this the likely option is a STM nucleo board with RIOT-OS as a embedded OS. | |||

| This choice is mainly because of previous experience and local knowledge of the operating system. | |||

+ 198

- 0

content/case_experiment_scara.tex

Ver arquivo

| @@ -0,0 +1,198 @@ | |||

| %&tex | |||

| As the previous development cycle was aborted prematurely, the development cycle is repeated for the next feature. | |||

| Starting with a feature selection process. Followed by the rapid development. | |||

| \subsection{Feature Selection} | |||

| The implementation of the end-effector proved to be unfeasible and was therefore removed from the design. | |||

| This means that only two features are left. | |||

| \autoref{tab:featurestab2} shows an updated feature comparison. | |||

| Compared with the previous feature selection in \autoref{tab:firstfeatureselection}, the number of tests for the \ac{scara} decreased and the Risk/Time increased. | |||

| This is because \autoref{test_tool_change} relied on both the \ac{scara} and the End-effector which is no longer applicable. | |||

| Based on the feature comparison, the next component to implement is the \ac{scara}. | |||

| \begin{table}[] | |||

| \caption{Comparison of the two remaining features in the design process. This table is an updated version of \autoref{tab:firstfeatureselection}.} | |||

| \label{tab:featurestab2} | |||

| \begin{tabular}{|l|l|l|l|l|l|} | |||

| \hline | |||

| Feature & Dependees & Tests & Risk & Time & Risk/Time \\ \hline | |||

| \ac{scara} & - & 2 & 50\% & 12 days & 4.2 \\ \hline | |||

| \ac{cdc} & - & 2 & 30\% & 10 days & 3 \\ \hline | |||

| \end{tabular} | |||

| \end{table} | |||

| \subsubsection{Evaluation} | |||

| The feature selection for the second cycle is an updated selection process of the first cycle (\autoref{sec:case_feature_selection_1}). | |||

| This resulted in a quick and effortless feature selection process, as most of the work was already done. | |||

| \subsection{Rapid Development for SCARA} | |||

| The goal is to present a functional model of the \ac{scara}. | |||

| The requirements state that it must be able to write three characters within two seconds. | |||

| And to pass \autoref{test1} it must draw a \SI{50}{\milli\meter} by \SI{70}{\milli\meter} rectangle within one second. | |||

| The basic design principle is based on the initial design as shown in \autoref{fig:combined}. | |||

| For the lowest detail level of the design, I decided on a kinematics model. | |||

| The model is very simple as it does not implement any physics. | |||

| However, the model enables me to tinker with the design parameters, such as the lengths of the linkages and joint angles. | |||

| In the following steps, the level of detail is gradually increased to arrive at a competent model. | |||

| Planning all the different steps in advance is difficult as design decisions still need to be made. | |||

| Nonetheless, I can describe at least the following levels of detail for the model: | |||

| \begin{enumerate} | |||

| \item Basic kinematics model, no physics. | |||

| \item Basic physics model, ideal 2D physics. | |||

| \item Basic Motor behavior, 2D physics with non-ideal DC-motor. | |||

| \item Basic control law, path planning. | |||

| \end{enumerate} | |||

| After these steps the optimal order of implementation for the levels of detail becomes vague. | |||

| However, the following elements are required to make a competent model: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item Improved motor model | |||

| \item 3D physics model | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| When the first design decisions made, the succeeding levels of detail for these and other elements are laid out. | |||

| \subsubsection{Evaluation} | |||

| The current steps in the rapid development are difficult to perform. | |||

| There is, unsurprisingly, lack of a clear vision of the end-product. | |||

| Which makes an explicit description of every level of detail not realistic. | |||

| However, it was still possible to describe the initial steps in the level of detail of the design. | |||

| The remaining elements, that are essential to the design, take shape in a later stage of the development. | |||

| Apart from this small deviation, the deliverables of this step are a good start of this development cycle. | |||

| \subsection{Variable Detail Approach} | |||

| The following steps is to increase the level of detail of the model. | |||

| The initial model together with the set of steps in the detail level is inherited from the previous design step. | |||

| To start, I implement the basic model and implement the different levels of detail. | |||

| Based on the model after those steps, it is possible to make more detailed design decisions. | |||

| The decisions make it possible to plan the subsequent levels of detail. | |||

| Implementing these details results in a competent model. | |||

| \subsubsection{Basic Kinematics Model} | |||

| \begin{marginfigure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=0.9\linewidth]{graphics/scara_arm_kinematics.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Basic kinematics of the \ac{scara}. The arm consists of two linkages $a$ and $b$; two joints $\alpha$ and $\beta$; and a point mass $m$ which represents the end-effector/tool.} | |||

| \label{fig:scaraarm} | |||

| \end{marginfigure} | |||

| The development starts with the basic model shown in \autoref{fig:scaraarm}. | |||

| The model consists of the forward and inverse kinematics of the design. | |||

| With this kinematics model it was easy to find a suitable configuration of the \ac{scara}. | |||

| I tested if the \ac{scara} reaches the required operating area, to satisfy system requirement 14. | |||

| The operating area is a couple of centimeters away from the base of the \ac{scara}. | |||

| This is to avoid the singularity point that lies at the base of the \ac{scara}. | |||

| Resulting in longer arms than strictly necessary but reducing the operating angles of the joints, allowing for simpler construction. | |||

| At this point, there are already multiple design decisions made about the position of the operating area and the arm lengths. | |||

| As second detail iteration the basic physics of the model are implemented. | |||

| The model is in the form of a double pendulum, with two actuated joints. | |||

| The ideal motors in the joints made give the \ac{scara} unlimited acceleration. | |||

| As the one of the goals is to get an indication on what the required torque for these joints is, the ideal motors are replaced with basic DC-motors. | |||

| Implementing a simple PID-controller allows the \ac{scara} to follow the rectangular path as described in \autoref{test1}. | |||

| The simulation allowed me to determine the minimum requirements of the motors. | |||

| The motors must be able to deliver at least \SI{0.2}{\newton\meter} of torque and reach an angular velocity of at least \SI{12}{\radian\per\second}. | |||

| \subsubsection{Detailed design decisions} | |||

| The basic model gave some valuable insight about the dynamic behavior of the system. | |||

| However, the current configuration is very simple but requires a motor in the joint. | |||

| In \autoref{fig:scaradesign}, this setup is shown as configuration 1. | |||

| The disadvantage is that a motorized joint is heavy, which has to be accelerated with the rest of the arm. | |||

| Other configurations in \autoref{fig:scaradesign} move the motor to a static position. | |||

| Configuration 2 is a double arm setup, but has quite limited operating range, caused by a singularity region in the system when both arms at the top are in line with each other. | |||

| Configuration 3 also has such a singularity, but due to the extended top arm this point of singularity is located outside of the operating range. | |||

| However, this configuration requires one axis with two motorized joints on it. | |||

| Even though this is possible, it does increase the complexity of the construction. | |||

| By adding an extra linkage, the actuation is split as shown in configuration 4. | |||

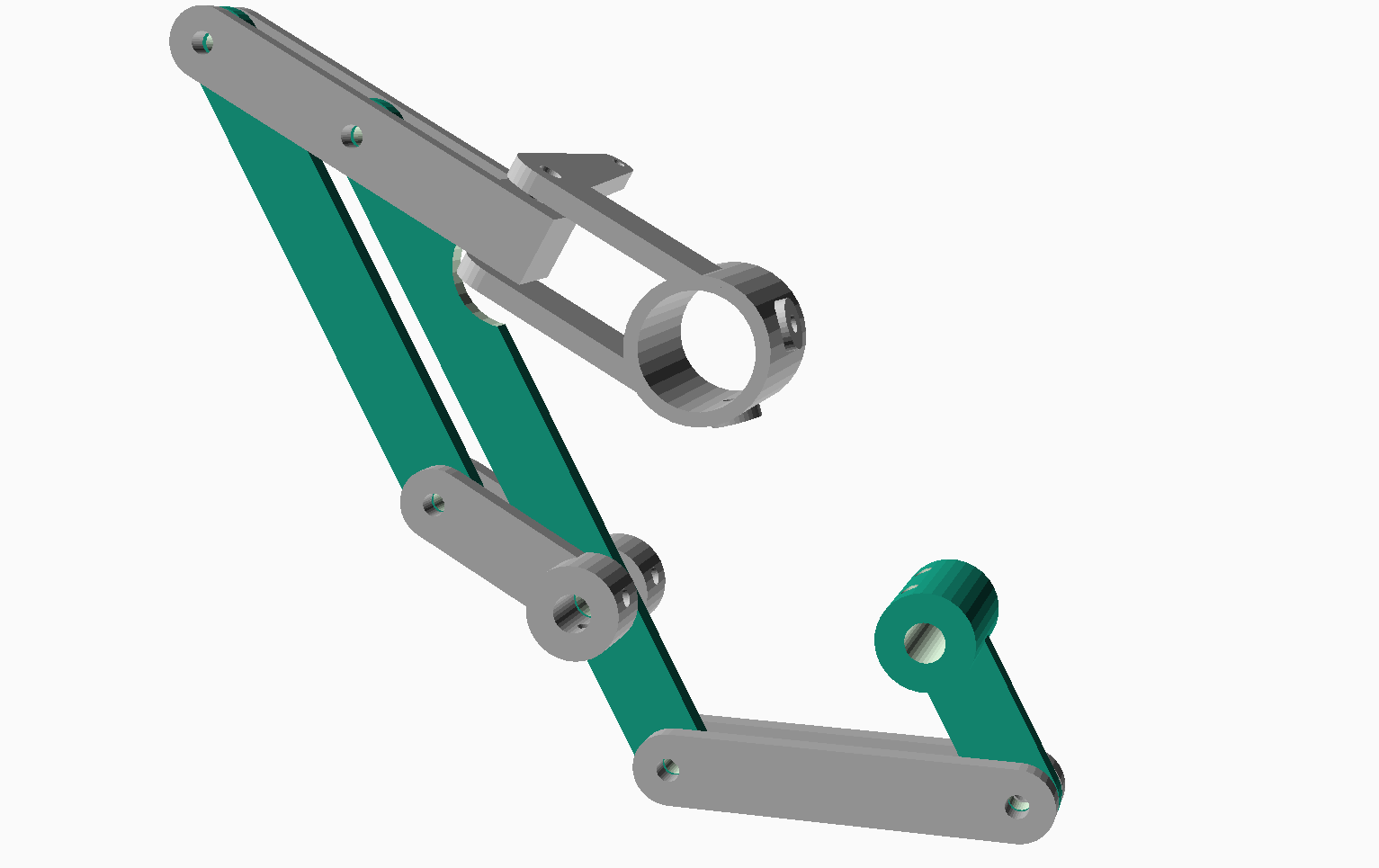

| Configuration 4 is the preferred option for the \ac{scara} | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=0.875\linewidth]{graphics/scara_design.pdf} | |||

| \caption{Four different \ac{scara} configurations. The colored circles mark which of the joints are actuated. Configuration 3 has two independently actuated joints on the same position.} | |||

| \label{fig:scaradesign} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| The actuation of the arm is done with stepper motors, which have a strong advantage over DC-motors with their holding torque. | |||

| The holding torque removes the need for a feedback controller that compensates for external forces. | |||

| Allowing the stepper motors to be fully operated with a feedforward controller. | |||

| However, they are heavier and more expensive but the additional mass is beneficial as increased inertia of the base. | |||

| The extra inertia reduces the displacement which is caused by the reaction force of the \ac{scara} accelerating. | |||

| The extra costs are easily compensated as it saves development time due to the simplified control law, and the removed need for extra angle sensors used in feedback control. | |||

| Due to the aborted implementation of the end-effector, the \ac{scara} must also lift the marker of the board. | |||

| With the fourth configuration (\autoref{fig:scaradesign}), it is possible to add an extra joint in the linkage. | |||

| As the marker only needs to be moved a couple of millimeters from the board, a simple hobby servo suffices. | |||

| \subsubsection{Advanced Detail Design} | |||

| The design decisions made in the previous sections, make it possible to plan the next steps of adding detail. | |||

| The following steps are an addition to the steps as described in the previous section: | |||