|

|

@@ -0,0 +1,265 @@ |

|

|

|

|

|

%&tex |

|

|

|

|

|

\chapter{System Design Method} |

|

|

|

|

|

\label{chap:systemdesign} |

|

|

|

|

|

\section{Introduction} |

|

|

|

|

|

This chapter explains the design method that will be used. |

|

|

|

|

|

The design method is build around the rapid-development methodology by \textcite{broenink_rapid_2019}. |

|

|

|

|

|

The rapid-development methodology consists of a structured way of implementing features consecutively. |

|

|

|

|

|

%proposes a methodology where features are implemented consecutively. |

|

|

|

|

|

The goal of the preparation phase is a list of feature definitions that are ready for implementation. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, it is expected that some features are not ready for implementation initially. |

|

|

|

|

|

Implementing the features that are ready, will generate more information about the design direction. |

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, the feature definitions will be reviewed during the development, each time the implementation of a feature is completed. |

|

|

|

|

|

During the review, feature definitions are updated with the additional gained information until ready for implementation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

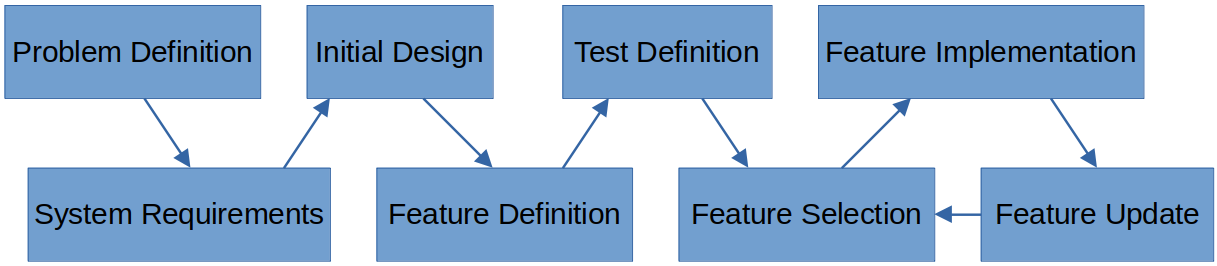

\autoref{fig:flowgraph} shows the different steps in the design flow. |

|

|

|

|

|

In this chapter the different steps are explained except for the feature implementation step, which is covered in the next chapter. |

|

|

|

|

|

\autoref{sec:preparation} explains the problem definition, system requirements and initial design. |

|

|

|

|

|

In \autoref{sec:featuredefinition} the feature definition step is explained. |

|

|

|

|

|

Then the system testing is introduced, followed by feature selection, as the test-cases will influence the feature selection. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\begin{figure} |

|

|

|

|

|

\includegraphics{graphics/flowgraph.png} |

|

|

|

|

|

\caption{Flow graph for the design steps. After a successful system testing the feature is completed and specifications are updated. Then the next feature is selected and implemented.} |

|

|

|

|

|

\label{fig:flowgraph} |

|

|

|

|

|

\end{figure} |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\section{Preliminary Design} |

|

|

|

|

|

\label{sec:preparation} |

|

|

|

|

|

The preliminary design is the first step of this design method. |

|

|

|

|

|

The steps in the preliminary design are expected to only be executed once. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, any mistakes made, could require a review of one or more steps of the preliminary design. |

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Problem definition} |

|

|

|

|

|

The first step of the design cycle is to describe the problem that has to be solved. |

|

|

|

|

|

A clear and concise problem definition increases a successful design process. |

|

|

|

|

|

It gives a better basis for the system requirements. |

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, lowering the number of reviews required for the system requirements. |

|

|

|

|

|

Furthermore, good definitions help determining overall feasibility of the project in an early stage. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{System Requirements} |

|

|

|

|

|

The system requirements are derived from the problem definition. |

|

|

|

|

|

As the features will be derived from these system requirements, the goal is to define the requirements without any ambiguity, vagueness or complexity. |

|

|

|

|

|

The requirements will be written according to \ac{ears} \autocite{mavin_easy_2009}. |

|

|

|

|

|

\ac{ears} was chosen for this design method due to its simplicity, which is is deemed suitable for the scope of this research. |

|

|

|

|

|

If issues, like ambiguity, are not dealt with correctly, these issues can propagate into the sub-requirements that will be defined for each feature. |

|

|

|

|

|

Solving these issues in a later stage of the design could require a redesign of features that were already completed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Initial Design} |

|

|

|

|

|

At the start of a development the final solution for the problem is unknown. |

|

|

|

|

|

It is important to explore the different solutions and design space. |

|

|

|

|

|

The goal of this initial design is to create an overview of these possibilities. |

|

|

|

|

|

Due to the scope of this research, the choice of design solutions is made for a design that is expected to fit this research, instead of determining the optimal solution. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

However, in an actual design case, this step is crucial and can even be extended. |

|

|

|

|

|

A problem can be solved with more than one design. |

|

|

|

|

|

It is expected that these design solutions contain identical features. |

|

|

|

|

|

For example, take a cube that has to be moved. |

|

|

|

|

|

Each design has a grab feature that picks up the cube. |

|

|

|

|

|

Instead of choosing a specific initial design, we could start by implementing the grab-feature. |

|

|

|

|

|

If the grab feature proofs to be infeasible, we know that we have to choose a different design. |

|

|

|

|

|

Would the grabber be a success, then the feature is already implemented for the designs that use it. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This can reduce the risk during the design by implementing features first that have overlap in other design solutions. |

|

|

|

|

|

First of all, it can help select a suitable design solution. |

|

|

|

|

|

If a initial design fails in a later stage, switching to a different design can be cheaper as some features are transferable. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\section{Features Definition} |

|

|

|

|

|

\label{sec:featuredefinition} |

|

|

|

|

|

The characteristics of the system under design are the system features, which will be implemented into the model. |

|

|

|

|

|

To implement the features one by one it is important that all the features are defined prior to the design cycle. |

|

|

|

|

|

A subset of the system requirements will be assigned to the feature and will be referred to as the feature requirements. |

|

|

|

|

|

The best division of requirements varies strongly with the domain of the system. |

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, the best engineering judgment of the developer is needed to divide the requirements. |

|

|

|

|

|

The sum of the feature requirements cannot exceed the overall system requirements. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, during the design phase it is possible to change the requirement division between features. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is expected that the division will be updated multiple times during the development. |

|

|

|

|

|

To efficiently change the division during the development without mistakes, good administration is key. |

|

|

|

|

|

\autoref{tab:subreq} shows an example to create overview. |

|

|

|

|

|

Each row contains one requirement. |

|

|

|

|

|

If a requirement is updated, the division can directly be reviewed. |

|

|

|

|

|

Would a feature change, then only one column has to be reviewed. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, the final organization of the different feature requirements is more complex than this example. |

|

|

|

|

|

Partially because not all requirements can be split up in simple numbers. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\begin{table}[] |

|

|

|

|

|

\caption{System requirements and the division of these requirements for features.} |

|

|

|

|

|

\label{tab:subreq} |

|

|

|

|

|

\begin{tabular}{ll|lll} |

|

|

|

|

|

& System & Feature 1 & Feature 2 & Feature 3 \\ \hline |

|

|

|

|

|

\multicolumn{1}{l|}{Weight} & 3 kg & 1 kg & 1.2 kg & 0.5 kg \\ |

|

|

|

|

|

\multicolumn{1}{l|}{Power} & 100 W & 25 W & - & 60 W |

|

|

|

|

|

\end{tabular} |

|

|

|

|

|

\end{table} |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Dependencies} |

|

|

|

|

|

\label{sec:feature_dependencies} |

|

|

|

|

|

Different features combined represent the complete system under design. |

|

|

|

|

|

How these features interact with each other is depending on the system design. |

|

|

|

|

|

For example, take a robot system that has to grab something. |

|

|

|

|

|

Looking at the two core features of the robot arm that moves, and the gripper that grabs. |

|

|

|

|

|

The specifications of the gripper could depend on the robot arm, as the gripper has to be compatible with the robot arm. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, this also applies the other way around. |

|

|

|

|

|

We could also specify a robot arm that is compatible with the developed gripper |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To ensure that the features are compatible with each other, the developer has to specify the dependency of the features. |

|

|

|

|

|

Especially in what direction the dependency should apply. |

|

|

|

|

|

Including extra system specifications to the robot arm example can result in a different dependency direction. |

|

|

|

|

|

If the specification is to lift an object with specific mass, the robot arm becomes dependent on the gripper. |

|

|

|

|

|

Because the robot arm has to be able to lift the mass of the gripper and object combined. |

|

|

|

|

|

If the specification would be a confined working area, the size of the robot arm is the leading factor. |

|

|

|

|

|

Which limits the remaining weight or size specifications for the gripper. |

|

|

|

|

|

If both specifications would apply, the developer has determine the dependency direction carefully. |

|

|

|

|

|

It is possible that the weight specification and space limitation combined lower the feasibility of the project. |

|

|

|

|

|

The developer should choose a direction which can determine the feasibility as early as possible. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This example used only two features. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, it is certain that the actual development contains more than two. |

|

|

|

|

|

\autoref{fig:featuredependency} shows an example of a dependency graph with five features. |

|

|

|

|

|

It can be seen that features 2, 3 and 4 are depending on feature 1. |

|

|

|

|

|

Where 4 is also depending on 3. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\begin{marginfigure} |

|

|

|

|

|

\begin{tikzpicture} |

|

|

|

|

|

[node distance=5mm,feature/.style={rectangle,draw}] |

|

|

|

|

|

\node at (0,0) [feature] (F1) {Feat. 1}; |

|

|

|

|

|

\node (F2) [feature,right=of F1] {Feat. 2}; |

|

|

|

|

|

\node (F3) [feature,below=of F2] {Feat. 3}; |

|

|

|

|

|

\node (F4) [feature,right=of F3] {Feat. 4}; |

|

|

|

|

|

\node (F5) [feature,below=of F1] {Feat. 5}; |

|

|

|

|

|

\path (F1) edge[->] (F2) |

|

|

|

|

|

(F1.east) edge[->] (F3.west) |

|

|

|

|

|

(F3) edge[->] (F4); |

|

|

|

|

|

\end{tikzpicture} |

|

|

|

|

|

\caption{Simple dependency graph for features.} |

|

|

|

|

|

\label{fig:featuredependency} |

|

|

|

|

|

\end{marginfigure} |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A crucial task in the design cycle is updating the feature specification accordingly with the dependency. |

|

|

|

|

|

At the point that the gripper is finished, the specifications of the robot arm can be updated. |

|

|

|

|

|

Not only does it improve the specification, it can also help in determining the feasibility. |

|

|

|

|

|

In this chapter we also introduce the method which selects the next to implement feature. |

|

|

|

|

|

This method does rely on the feasibility and dependency of features, making the update even more important. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\section{System Testing} |

|

|

|

|

|

\label{sec:systemtesting} |

|

|

|

|

|

The system and features are tested during each iteration against the system requirements. |

|

|

|

|

|

This is to make sure that the design still performs as expected. |

|

|

|

|

|

During the preliminary design phase of the development the system tests are defined. |

|

|

|

|

|

The system test are derived from the system requirements and cover the global performance. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, at this point there is no model yet to test against. |

|

|

|

|

|

During the design cycle these test cases will become valid as more behavior of the system model is implemented. |

|

|

|

|

|

For each test it is assessed what features are required to complete the test. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

%Although an automatic testing method is presented by \autocite{broenink_tooling_2020}, the testing will performed manually. |

|

|

|

|

|

%The tooling is still experimental and yet suited for use in a design method. |

|

|

|

|

|

The tests that will be done cover the physical part of the system. |

|

|

|

|

|

These tests will be performed manually as tooling for automated testing is still in the experimental phase. |

|

|

|

|

|

\rrot{@Tim, I like to cite the paper on AMT but that one is not yet published?} |

|

|

|

|

|

However, a design of a cyber-physical system is guaranteed to contain software. |

|

|

|

|

|

As the focus of this Thesis is on hardware design, the software testing will not be part during this research. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\section{Feature Selection} |

|

|

|

|

|

This section explains the selection criteria which determines the next feature that will be implemented. |

|

|

|

|

|

During the development it is expected that problems and issue occur. |

|

|

|

|

|

The consequences of these issues are that a system requires a (partial) redesign. |

|

|

|

|

|

Worse, the problem cannot be solved and the development is cancelled. |

|

|

|

|

|

The selection method is designed to reduce the risk of these issues during the development. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Dependency} |

|

|

|

|

|

\autoref{sec:feature_dependencies} introduced the dependencies of features. |

|

|

|

|

|

By the fact that child features are missing information from the parents implementation, the parents shall be implemented first. |

|

|

|

|

|

Even if the child is not relying on parent information, the parent should still be implemented first. |

|

|

|

|

|

If the parent feature is not feasible, any implementation of the child becomes obsolete. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parent-features with multiple children have priority. |

|

|

|

|

|

As the implementation gains new knowledge that is relevant for multiple features. |

|

|

|

|

|

This helps to get all the specifications defined in an early stage of the development, which reduces the risk. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Test Completion} |

|

|

|

|

|

Each function has a set of requirements which are tested during the development. |

|

|

|

|

|

This is a subset of the system requirements. |

|

|

|

|

|

\autoref{sec:systemtesting} explained the system tests, where the system tests can span over multiple features. |

|

|

|

|

|

Passing these test is crucial for the design method, as finding flaws in an early stage is very important. |

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, features that can make a requirement testable can be selected by the developer to be implemented first. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Risk Assessment} |

|

|

|

|

|

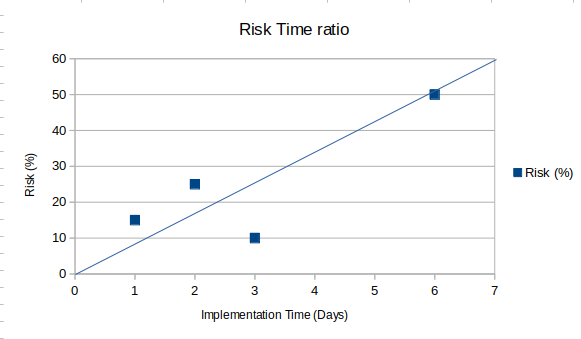

It is important to clear the risks in a development in the shortest amount of time. |

|

|

|

|

|

If a development runs into problems near the end of its completion all investments are lost. |

|

|

|

|

|

All features will be ranked on their feasibility and time required for implementation. |

|

|

|

|

|

With that it is possible to sort the features such that most risk is cleared in the least amount of time. |

|

|

|

|

|

%Remaining features from both selection criteria are sorted on risk and implementation time. |

|

|

|

|

|

%When features are implemented and test are complete the risk of them failing is gone. |

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, features that are quick to implement could have priority, as the risk can be cleared in an early stage. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, there is a trade-off to be made with risk involved of the implementation itself. |

|

|

|

|

|

Features with a low feasibility are a risk to the whole development. |

|

|

|

|

|

Especially if the feature has low feasibility and a large implementation time, a large risk remains at the end of the development. |

|

|

|

|

|

Combining time and risk factors gives a method for eliminating the highest risk per time of development. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In \autoref{tab:risktimetable} a situation of four features is shown. |

|

|

|

|

|

It can be seen that feature 1 has the highest risk. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, by prioritizing features 3 and 4 over feature 1 we can clear 40\% of the risk in halve the implementation time of feature 1. |

|

|

|

|

|

\begin{table}[] |

|

|

|

|

|

\caption{Comparison of features with their corresponding risk and time. The last column is the risk value divided by the number of days.} |

|

|

|

|

|

\label{tab:risktimetable} |

|

|

|

|

|

\begin{tabular}{l|l|l|l|} |

|

|

|

|

|

\cline{2-4} |

|

|

|

|

|

& Time (days) & Risk (\%) & Risk per time \\ \hline |

|

|

|

|

|

\multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. 1} & 6 & 45 & 7,5 \\ \hline |

|

|

|

|

|

\multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. 2} & 3 & 15 & 5 \\ \hline |

|

|

|

|

|

\multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. 3} & 1 & 15 & 15 \\ \hline |

|

|

|

|

|

\multicolumn{1}{|l|}{Feat. 4} & 2 & 25 & 12,5 \\ \hline |

|

|

|

|

|

\end{tabular} |

|

|

|

|

|

\end{table} |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Combining} |

|

|

|

|

|

\rro{Example of a selecting features with the three methods given above} |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\section{Feature Implementation} |

|

|

|

|

|

This section will explains the methodology for the development of a single feature. |

|

|

|

|

|

The methodology is based on the variable detail model simulation methodology \autocite{broenink_variable_2018}. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Initial design} |

|

|

|

|

|

Implementing a feature starts with an initial design. |

|

|

|

|

|

The initial design gives a rough idea on how to implement the feature. |

|

|

|

|

|

This is important because there are multiple ways to implement a feature. |

|

|

|

|

|

For example, moving a carriage along a rail can be done by a belt drive, hydraulics, rack and pinion, or any other form of transmission. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\rrowip{General Note: This part of the method never felt like I could fit it in. Now that I have applied the method in general it does make even less sense...} |

|

|

|

|

|

From the initial design the structure of the model is determined. |

|

|

|

|

|

The structure of the model specifies different sub-models in the system and how they are interconnected. |

|

|

|

|

|

\textcite{broenink_variable_2018} explains how to split the model into sub-models. |

|

|

|

|

|

Broenink's methodology also introduces different categories for the elements. |

|

|

|

|

|

Where the first step is to implement only the essential elements. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, which elements are essential has a strong dependency on the type of feature. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Testing} |

|

|

|

|

|

To make sure the design of the feature stays within the specifications, the model is tested continuously. |

|

|

|

|

|

The test-cases are based on a set of system specifications that was assigned to the feature. |

|

|

|

|

|

\rrowip{Although AMT would be really nice it was not feasible to implement/use it. Therefore, it was done manual and I have to remove this part.} |

|

|

|

|

|

Similar to the system testing in \autoref{sec:systemtesting} the test are performed with \ac{amt}. |

|

|

|

|

|

It is important that the feature specifications are tested. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, the test should also cover the physical behavior like parasitic elements. |

|

|

|

|

|

It is obvious that we have to test this, but no clue on how to actually test. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Making the test cover all the physical behavior is expected to be impossible. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, without a coverage case for physical behavior it is possible to create a model that checks all the tests. |

|

|

|

|

|

For example, by leaving out the parasitic elements and only using ideal elements. |

|

|

|

|

|

This does not mean that the model is competent, but it shows that a model can ignore the laws of physics. |

|

|

|

|

|

So the challenge is to complete all the tests with a model that remains a realistic implementation. |

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, modeling a realistic behavior is task of the developer. |

|

|

|

|

|

And this is eventually validated with a physical prototype. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Model detail} |

|

|

|

|

|

\rrowip{This part is a bit minimal, needs more content} |

|

|

|

|

|

The initial idea was to start with an ideal model as first implementation. |

|

|

|

|

|

It is expected that implementing only the essential elements of the system does not represent a valid behavior. |

|

|

|

|

|

At least not with the categorization that is introduced by \textcite{broenink_variable_2018}. |

|

|

|

|

|

Maybe in a simple motor model, but not in a system with some kind of feedback. |

|

|

|

|

|

As the feedback is normally based on the state of a storage element. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The order of implementation is difficult to define. |

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, it should be the developer that decides on the minimal implementation of the model. |